0004 | January 22, 2018

Public Outrage: Part II

C. Travis Webb and Seph Rodney continue their discussion about public outrage. Does expertise bring wisdom? Is outrage at elites justified? This and much more is discussed in this second of a two part discussion.

| C.T. WEBB 00:00 | [music] Hello, welcome to The American Age broadcast. Today, we will be continuing our discussion about public outrage, public anger. And if you tuned in last time, we were in the midst of our conversation and agreed early on that we would pick up in a part two because there was lot to unpack, as I’m sure is unsurprising to anyone that at all pays attention to social media or media – mainstream professional media. And Seph’s going to lead us in because he has some stuff to say, and we’ll begin. Seph, welcome. Good to see you. |

| S. RODNEY 00:49 | Thanks, good to see you. I wanted to pick from where we left off in the conversation last time, but I won’t exactly because I think where we left it was at the place where we were about to talk about what I think are the important points that Glenn Greenwald made in his article for The Intercept. But I actually want to start by talking about this moment in the conversation when I gave the anecdote about attending a particular performance, Shaun Leonardo’s, and how the activists responded to me, essentially saying that I believe that there were things that they did that reminded me of supporters of our current president. |

| S. RODNEY 01:37 | I should have admitted – and I think it’s really important to do so – that I was angry. That at the time I wrote that, I was acting from anger. And I do think, again, that my characterization of them was not wrong, was not inaccurate. But I have to acknowledge that there is a way in which I think anger begets anger. Mind you, at the same time, I think lots of things beget anger. I think complicity begets anger. I think being humble begets anger. I think there’s a way in which American public culture– all the things that you mentioned in your initial talk, your initial introduction tonight, social media, other forms of media, particularly mainstream news outlets, anger seems to dominate the ways that we respond to each other in the public sphere when we disagree. Mind you, when we don’t disagree, that’s all well and good. But I want to say, one, we’re capable of much more nuanced responses than just anger or pleasure. I mean, goddammit, we’re adults. We’re adult, semi-rational human beings most of the time. |

| C.T. WEBB 03:27 | One would hope. |

| S. RODNEY 03:28 | Yeah. Semi-rational, right? So I’m hedging it already. We can do more than simply say, “You suck,” or some version of– well, most of time, what we’re actually saying is, “You’re illegitimate.” That what you are and what you say is not valid. And I think we need to get away from that. |

| C.T. WEBB 03:53 | Yeah, I agree. So I wanted to kind or rhetorically bookmark something I’d like to come back to, because when you had initially sent me the topic for discussion, the first thing I thought of was a book by Mary Douglas called Purity and Danger of the Anthropologist. And she has this whole grid argument and looks at Leviticus in the Old Testament and comes up with this schema which she honestly, later strongly amended, but in a preface to the book 20 years later, which is essentially this– and I’m going to broaden this out in a second. Dietary prescriptions, as in, “Don’t eat milk and eggs at the same time,” whatever, but keeping kosher laws– I think I just butchered that, so I apologize to all of my Jewish listeners. But that basically– |

| S. RODNEY 04:52 | I think it’s milk and meat, basically. |

| C.T. WEBB 04:54 | Yeah, no– |

| S. RODNEY 04:54 | No milk or meat, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 04:56 | Milk of the kid and all this stuff. But basically, what this was a way doing was to demarcate the community. It’s a more complicated argument than that, and it’s a compelling argument. But for the purposes of this, it is a way to set aside who we are from other people. And there a way in which that indignation that one feels at someone using the wrong word at the wrong time, and the kind of prick that that provokes, and the moral outrage that follows is a way of demarcating communities. So let me just bookmark that for a second. That was the first thing I thought of when you asked that question. I actually want to go back and ask you a more direct, personal question. Why were you angry when you wrote the Shaun Leonardo piece? |

| S. RODNEY 05:56 | Well, to be clear, I was partly angry at the activists. I was also quite taken with the work that Shaun had done. And by taken with, I mean, I felt emotionally supported. I felt seen and recognized by him. The performance, again, to just reiterate in case listeners who are listening– |

| C.T. WEBB 06:30 | The crazy [crosstalk] possibility that the people did not listen to our previous podcast. |

| S. RODNEY 06:34 | The previous one, right. Basically, in this performance, he taught people skills, techniques of getting out of a chokehold or dodging a punch and getting away – essentially, survival techniques particularly geared towards people of color and women in neighborhoods that are beleaguered, that are under stress. So part of the piece was very much embedded in that feeling of finding someone who was essentially expressing care for me, and I really, deeply– |

| C.T. WEBB 07:14 | Oh, that’s wonderful. |

| S. RODNEY 07:16 | Yeah. I deeply appreciated that, so I wrote most of the piece that way. Why I was so angry– |

| C.T. WEBB 07:20 | Can I ask [crosstalk]? |

| S. RODNEY 07:22 | Go ahead. |

| C.T. WEBB 07:22 | Can I ask [inaudible]? In a fatherly way, right? Which is also something, a kind of engagement– |

| S. RODNEY 07:27 | Yeah, go ahead. |

| C.T. WEBB 07:29 | You don’t agree? I was going to say, is a kind of an engagement that I think there is a dearth of in Western culture right now– |

| S. RODNEY 07:38 | Well, it’s– |

| C.T. WEBB 07:40 | So I’m sorry. Go ahead. |

| S. RODNEY 07:41 | It was certainly among men, right? And I’m not sure that I’m willing to call it fatherly. I felt like it was brotherly, even though I don’t have a brother. I think you and people like Lawrence and Damien have been some of the men in my life who have come as close to that as possible. But I felt a nurturing there, a nurturing attitude. So– |

| C.T. WEBB 08:06 | Fathers can be nurturing. |

| S. RODNEY 08:08 | Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Right, but there’s a kind of mentorship kind of relationship implied by the term father, and I didn’t feel [crosstalk]. And even though he was kind of mentoring me – he was teaching me something – I didn’t feel that. I felt it was more– it just felt more horizontal rather than sort of vertical, is the easiest way to– |

| C.T. WEBB 08:33 | That makes sense. That makes sense to me. |

| S. RODNEY 08:36 | Right. So why I was so angry was that they expressed contempt for the other opinions in the room, not only mine. And I saying something about thinking differently about policing to just make it short. But when I saw the other woman next to me hesitate, she said something about her own identity and how she felt that that wasn’t being validated in certain circles. And the way the woman on stage responded to her– she wasn’t really on stage. She was at the center of the room. She was essentially holding court. The way that that woman responded to the woman who was next to me was contemptuous, and that made me angry. Because I thought one, how is it possible for you to represent yourself as activists who are in a position to care for, to guide a community towards essentially some greater freedom? That’s what you want to do, right? |

| C.T. WEBB 09:53 | Was there any racial coding going on with the woman that was in the center with you that was holding court? Was she white? Was she–? |

| S. RODNEY 10:02 | She’s black, but she spoke as if– I think she actually said there with three activists. There was Shalene Rodriguez, and there was this one whose name I’m not remembering anymore, and a third person named, I think, Al Tindor, a man. The older woman was just contemptuous, and the conversation was racially coded in that she had lots of things to say about how we should refer to black and brown people. She was saying something about the term “people of color” wasn’t exactly kosher with her, whatever. The point being that there was a response from her that essentially invalidated all the other responses in the room that– |

| C.T. WEBB 10:59 | Contempt, you called it last time contempt. |

| S. RODNEY 11:01 | Yeah, yeah. And she was contemptuous about it. And that makes me angry. It makes me sad and angry, but my response was anger primarily to that because that is precisely the opposite of what I think they are purporting to do in that moment. And it’s also personally for me just really hard to deal with, because my father was treating me with contempt at certain key points in my childhood, and that I’m still in some ways, I suppose, wounded by that. So it’s important for me to acknowledge that as well. |

| C.T. WEBB 11:43 | Yeah. I mean, I think to take a step back and sort of just look at it from a more anthropological point of view. I mean, we’re prosocial primates, right? So we are particularly calibrated to pick up on iniquity and to either internalize that registration to react against it, to provoke us in whatever way that we happen to provoke it and in whatever way it happens to be provoked. So you brought up your father. And obviously, that is a particularly intimate relationship, and that happens. You’re a kid. You’re particularly vulnerable. You don’t have your armor yet, right? So when you’re an adult, you’ve got your sword and your shield and your armor. You’re like, “Fuck this, fuck them, fuck that,” right? But when you’re a kid, you’re pretty exposed. You don’t have those things. And so really, the chances of that becoming internalized, that becoming some kind of internal narrative about yourself and about your place and position in the world. I mean, this is one of the– and not to get sidetracked, but I mean, this is one of the things that I am most sympathetic– even though on practice, I want to say, “Okay, what now?” when it comes to someone putting all their chips in on racial politics, anti-colonialism, these kind of arguments. |

| C.T. WEBB 13:19 | Actually, I’m very sympathetic to those arguments because what must that be like to be a group of people that are circumscribed and defined in such a way as they are understood internally and externally as being less than? Do that for 200 years, 300 years, 400 years, and you fuck some shit up. This is not a recipe for an empowered, reasonable engagement with a group of people. |

| S. RODNEY 14:03 | I agree. |

| C.T. WEBB 14:03 | So I have a lot of sympathy for that, and not just sympathy. I get that. So okay, fine. So let’s bring it back to your interaction with the activists in Shaun Leonardo, and let’s grant that– and we’re going to bracket for a second whatever interpersonal, internal, psychological issues might’ve been going on with those other activists and how haughty they felt and how contemptuous they were. Let’s say that they were fully honestly, reasonably expressing three or four hundred or years of outrage. All right, let’s just grant them that. What next? This is what I feel like– this is where I feel like your indignation comes from. I mean, being someone that is imminently reasonable and sensitive, okay, what do I say now? Where do we enter this conversation together to–? |

| S. RODNEY 15:06 | Or even more forward looking, where are you going now? What do you want to do with this community? Because you say things that are provocative and noncanonical like, “We need to end all policing in our neighborhood now, because the police aren’t an occupying force.” Great. |

| C.T. WEBB 15:31 | That’s nonsense, by the way. |

| S. RODNEY 15:32 | Right, right. No, no. No, I’m with you. Same page, same sheet of music. My question is, “What are you going to do now? If you really want to hold hands with this community and lead them out of the wilderness they’ve been in for not 40 years, but 300 years, how are you going to do this?” My indignation comes from this place of I respond to contempt, but I also respond to injustice – response, as you say, to injustice – to feeling like they were being unjust to other people in the room. And also, to a sense of just sheer bewilderment and indignation that you would present yourself as someone who’s willing to do this work, but then you show up in the room, and you don’t do the work. You do something else, but you call it activism. That’s dishonest. |

| C.T. WEBB 16:26 | Slacktivism is what someone much younger than me told me. I mean, it’s not that I’d never heard this term, but we were discussing what to do with a project that we’re starting. It’s about philanthropic educational engagement, and she was saying– she’s in her 20s, and she was saying that a lot of her friends– and fairly well off, privileged backgrounds, but these are people that are people that they’re engaged. They want to do something good. They want to make something in the world that is edifying within the world. And she went off for a few minutes about this issue of slacktivism, and she caused me to think about it for a– to pause and think about it. That there really is, there is a concrete difference between expression an opinion, between venting or advertising moral outrage and doing the work to rectify the iniquity that has pricked your conscience. Right? There’s a difference. There’s a risk involved, what Stuart Hall used to call the contingency of failure. Right? |

| C.T. WEBB 17:43 | We might fail. We probably will fail. It’s probably not going to work out, so the Civil Rights marches– and that was in the ’60s. But this was after 100 years of people speaking out and not riding in right section of the bus, and sitting at the wrong counters, and expressing moral indignation or outrage. I mean, this is one of the things that bothers me about contemporary public discourse, is they want to localize the activities too much. As if Martin Luther King just sort of appeared, ex nihilo. Just like, “So here I am as the savior.” I mean, I know you like to bring– I mean, it’s really kind of the Judeo-Christian idea, right? So God’s finger comes down and inseminates some humans, and wisdom spreads out into the world. But no, I mean, King came out of an Atlanta that had for 100 years– not quite 100 years, but had built a strong black community around economic success and pride and engagement. And that’s what he came out of, right? I mean, that culture that empowered people to act in the world in that way. |

| C.T. WEBB 19:06 | And when I look around at my contemporaries, when I look around at my peers – whether it’s in the academy or whether it’s maybe peers that I don’t know, but that are writing for The Atlantic or The New Yorker or something like that – where are you engaging? What is your work in the world? Not just what are your opinions? I can have the shiny opinions too. I know the right fork to use at the table, but what are we doing to engage with one another? |

| S. RODNEY 19:46 | Well, I think that’s precisely the question that needs to be posed to Glenn Greenwald, I should say, for this article in The Intercept. Because here’s– |

| C.T. WEBB 19:54 | Can you give us the title of the article? |

| S. RODNEY 19:57 | Sure. Actually, I don’t have it written here. I can find it and– |

| C.T. WEBB 20:05 | I have it, because I read it right before we got started. So the “Petulant Entitlement Syndrome of Journalists”, and that’s January 28th, 2015 in The Intercept. |

| S. RODNEY 20:16 | Okay, great. So basically, he takes a [inaudible] out of Jonathan Chait’s “denunciation of the PC language police.” But where he ends up is precisely this place where I think the question is begged, the question that you’ve posed. Because where he ends up is– he says, and I’ll quote him. It’s the third paragraph from the end. “It also proves that one of the best aspects of the Internet is that it gives voice to people who are not,” emphasis is, “credentialed – meaning not molded through the homogenizing grinder of established media outlets.” Now here’s the thing for me, he’s partly right. Whenever I hear a congressperson – senator or representative, in some cases, people from statehouses, governors and on down – speak publicly, I don’t know what to do with myself. I’m so angry. I’m pushed to despair because they don’t say anything. They don’t say anything of worth. |

| S. RODNEY 21:30 | “Yes. Well, this legislative process is just going through. The wheels are turning. We’ve got to get these members on the floor to discuss this, and that’s the only way that this initiative is really going to get anywhere.” So they asked him a direct question, so Senator Paul Ryan, “How is it possible to get this legislation for the Dreamers passed if the President, the person who’s the figurehead of your party, expresses opinions that appear to be racist?” And he answers, “Well, well, look. I mean, there’s no way that we’re going to get anywhere on this question. If we just go around calling the President racist, I mean, that’s just not possible.” You’re not dealing with what’s in front of you. You’re not actually engaging with me, if I’m posing a question to you. What you’re doing is you’re deflecting, avoiding, and you’re just reading from a script that you want to read, that you want to disseminate publicly. |

| S. RODNEY 22:39 | So Glenn Greenwald has a point in that people who are not credentialed do sometimes have the intellectual wherewithal to frame situations, to respond to questions, to decisively describe the thing that is happening to us right now in ways that are actually insightful. And I’m thinking of the comedian, actually, Russell Brand. He appeared on Morning Joe, I think it was, and he was devastating. |

| C.T. WEBB 23:17 | I know. |

| S. RODNEY 23:18 | He was devastating, because he cut through the bullshit. He said, “Look at the kind of question you’re asking me. Look at the kind of conversation you expect us to carry on. This is just– it’s entertainment. You want me to be the dancing bear, and I don’t want to do it. So– |

| C.T. WEBB 23:36 | You know what I remember from that appearance was Mika Brzezinski was basically giving a handjob to the cup she had in front of her, which he called her out on, which I thought was– it gave me a lot of joy. I thought that that was quite funny that he did that, so– |

| S. RODNEY 23:52 | Yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So Greenwald has a point, but my problem is that most of the people– from what I can tell, reading the comments, and being in media, and having to deal with people who respond to what I’ve written on the Hyperallergic site, most of the people, it seems to me, who are not credentialed come from this place of not being particularly one, rigorous with their thinking and two, clear about what they want. |

| C.T. WEBB 24:24 | I have to say, amongst credentialed people, I haven’t seen a whole lot of clarity about they want either. I mean, I think when you follow a lot of arguments that are– maybe in vogue is too strong. Certainly, in vogue 10 years ago, 20 years ago, but definitely still regularly bandied about at conferences. And I’m talking fill-in-the-blank, Foucault power– |

| S. RODNEY 24:53 | Yeah, Derrida and différance and logocentrism. |

| C.T. WEBB 24:59 | Yeah, yeah. It’s all around. It’s all out there. I don’t really feel like there’s a whole lot of thinking through anywhere. I think it’s a stranger to every social group I know. Thinking through and actually having a coherent worldview that potentially implicates one’s self in the hot mess that is human culture making, it’s uncommon. It’s uncommon for everyone. And I have to say– and I know that you actually agree with this. We’ve had conversations around this. So I mean, I think your indictment of kind of uncredentialed, half-baked thinking– of course, I buy that. I know that’s true. I read the [inaudible]. I read some of your articles. I see some of these comments. I engaged with one of them one time – I remember this a couple of years ago. But I also find a great deal of intelligence and sobriety and wisdom amongst people that don’t have letters after their name. And just– |

| S. RODNEY 26:09 | Like who? |

| C.T. WEBB 26:10 | Specific people that I’ve met? |

| S. RODNEY 26:13 | Yeah, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 26:14 | So my parents, for example, I mean, this is starting to get a little too personal, but other people aren’t necessarily going to care. But yeah, I mean, my dad came from nothing. I don’t mean my dad came from nothing, he worked himself up, and he’s an oil tycoon or some bullshit [crosstalk] story like that. My parents, they struggled with financial discipline – I mean, all the rest of of it. But my dad came from some fucked up shit, just bad news, and he made– one of the things that I get tired of, I get a little tired of kicking around middle-class aspirations. This is something you get from Slavoj Zizek and stuff like that. “[crosstalk] middle class, empty coke bottles, and elevator [laughter] doors that don’t work appropriately,” or whatever Daffy Duck bullshit he throws at the wall to see if it sticks. You know what? There is nothing wrong with middle-class aspirations. |

| C.T. WEBB 27:14 | My parents loved being at home. They loved their house. And you know what? I wish that for all people. Everyone that wants that, I want that for them. And the people that don’t, I don’t feel like they should be looked down on for not wanting that. If you want to live in a fucking commune and share your children and your genitals, I don’t care. I feel like you should have space to do that. Buy some property. Do whatever you need to do. It doesn’t make any difference to me. So you asked specifically, so my parents. And I could probably name some other people, if we had time and we weren’t dealing with a finite amount of time with the podcast. But I find wisdom, and I hesitate to use it because it’s a word that borders on cliche in intellectual circles. But fuck that, I think it matters. And I think that wisdom does not visit any group of people frequently. And I don’t care how much education you have. I don’t care how well you understand the Maafa or the Holocaust or the subjection of peoples across South Asia. Wisdom does not come at the end of that. Wisdom comes from humility. |

| S. RODNEY 28:41 | Yeah, I hear you. I hear you. And for the most part, I agree with you. I do think that– I think again, several people in my life who I would tend not to rely upon or go and seek advice from, precisely because I don’t think that they’re humble enough. I think that they have a rather overblown sense of they are and how important they are. And I think really, this is coextensive with my worldview and with the things that I need in order to operate well. I prefer to have distinct sentences, recognizable, plucked out of the swarm of white noise. And there’s a swarm of white noise online and in public forums these days that I don’t think ultimately benefits that quest for wisdom. I tend to want to call it rational discussion, but I think we’re about very similar things. So let’s use the word “wisdom”. I think that there’s actually a– is it a cliche or saying, something like that? Oh, no, no. No, I’ve got it. I remember now. Farid told this story about being– |

| C.T. WEBB 30:30 | Farid Matuk is a friend of ours who teaches poetry at University of Austin [crosstalk]. I’m sorry, University of Arizona. Went and got his MFA at the University of Austin – University of Texas at Austin, sorry. |

| S. RODNEY 30:41 | Right. So he’s told me the story about Philip Levine, being at a meeting of his, and this is before the Iraq war. And it was after the meeting, and he was taking questions and responding to people in the audience. And some guy said, “Well, don’t you think,” la, la, la, “Bush is correct? And we’ve got to head this off at the pass. And these people are part of the triangle of evil, access of evil [laughter], the poly [crosstalk] of evil. |

| C.T. WEBB 31:09 | The triangle [laughter]. The isosceles. |

| S. RODNEY 31:12 | What is it they have? |

| C.T. WEBB 31:13 | Demonism or whatever. |

| S. RODNEY 31:14 | Right, right, whatever. And Philip Levine said– I forget exactly what Farid told me he said, but it was a very harsh response. He basically said, “You need to shut up and sit down because you don’t know what you’re talking about.” And then, he ran through and ticked off reasonable points for opposing the war. Which in hindsight, duh. But then, the man sat down, and he went on. And then, he came to him. Philip Levine came back to the man. He said, “Actually, I need to apologize. What I said, I said in anger. And my anger prevented me from–” and what was the word? I think used the word “insight”. “My anger prevented me from–” no, clarity. “My anger prevented me from clarity.” |

| S. RODNEY 32:17 | I really want to get to the place in our culture where we can recognize that distinction. That you can be angry, and reacting from anger is not necessarily always bad. But once it trips over into contempt, once you lose sight of the thing it is that you want– and maybe I’m being too generous. Maybe I’m assuming that people do want to get to a place of [inaudible]. Maybe they don’t. Maybe they just want to be angry– |

| C.T. WEBB 32:49 | Because there’s pleasure in indignation. I mean, there really is. There’s real pleasure in moral indignation. |

| S. RODNEY 32:55 | Yeah, yeah, yeah. And the sort of end of the spectrum of that or one end of that continuum is the person is so angry that they take up an AK-47, and then they go into a church and blow everybody away who they think is standing in the way of their fulfillment or happiness. I do think that being we can– being credentialed is not a panacea. It will not cure our social ills. I’m not sure what will. In fact, I have to admit that I’ve come to a point in the conversation where I’m actually really frustrated with myself, because I’ve kind of hit a brick wall. Right? There is nothing I can prescribe to heal the body politic. There’s a way in which– and I’m reminded of this moment in Mad Men, the TV series, where Don Draper’s character says to– or rather Don Draper, the character played by– what’s his name? |

| C.T. WEBB 34:09 | Jonathan Hamm, I think is his name. |

| S. RODNEY 34:11 | Thank you. Hamm says to the character played by Elisabeth Moss, who at some point, was his secretary. He says, “There’s something in the American spirit that is broken, and you recognize that.” And here, he’s telling her why he wants her to come back to work for him, why he needs her in his– why he needs her insight. He says, “You see it. You see the thing that is broken.” And I feel that he put his finger on something, that there is real– and maybe it amounts to this. Ever since the ’60s, what we’ve had coming to us is a kind of demographic change that is apace with a social change, a deep social change. I mean, we could talk about this in different ways, but it’s actually the end of white male supremacy. And I think there’s a lot of anger being generated around not just that deep social change, but all the sort of corollary sort of ripples that come out of that wave. |

| C.T. WEBB 35:25 | So yeah. I mean, I think there’s a lot to recommend what you just said, and I basically agree with a lot of that. I would probably want to take it a step further and say that white heterosexual male supremacy, right, because we probably need to add that in as well– heteronormativity is clearly something that is at the center of culture for a long– at the center of American culture, Western culture for a long time. That it not only devastated white people and how they made sense of the worlds. It devastated everyone, because if you don’t have Malcolm X’s “white devil” or I guess, Elijah Muhammad’s “white devil”, right? Malcolm X sort of drifted from that, although not as much as people would like. But Alex Haley kind of softened that, from what I’ve read from historians. But that the world is simpler when you have an adversary. There’s a reason that Manichean religions survived for so long in Central Asia. There’s a reason that that was taken up, and I’m talking about Zoroastrianism. There’s a reason that that was taken up, although there were other Manichean traditions too. But there’s a reason that was taken up and served as the kernel of– Judaism moved away from it. Christianity picked it back up. Islam revived it. |

| C.T. WEBB 37:08 | An enemy clarifies things, right? At no point in the last 100 years was it more clear to be an American than in 1942, in 1941. You knew you were– even if you were African American, even if you were on the underside of what America represented, your ass was in the trenches getting shot at by Germans, if you were an able-bodied male at that age. So an enemy clarifies in us and them, and there is a kind of servitude and calm that comes from knowing one’s relationship to others because it’s a very scary place to be, I mean, for all of those existential reasons that the French are so good enumerating. And when you take that away, so you pull– I mean, because yes, it’s– and this is something obviously, that we would get pushback from or you may push back against it as well. Clearly, white males still over-represented in statehouses, in federal houses, in pews and judgeships. And I’m not saying that white heteronormativity and masculinity is not at the center still, but we mentioned this in other podcasts, it’s clearly under a threat. |

| C.T. WEBB 38:41 | Its perch is more precarious. And most importantly– and I don’t think that this can be dismissed, and I don’t think it can be ignored, though it is often glossed. No one, not even our current President can make a white heteronormative, masculine argument. He has to hide, he has to conceal what his actual worldview is, what his epistemology, his metaphysics, his ethical system. That has to be obscured. That– |

| S. RODNEY 39:15 | That’s right, because it’s no longer valid– |

| C.T. WEBB 39:16 | That’s right. That’s huge, huge, huge. The fact that George [inaudible] cannot write– what was the name of his book? I won’t spend any time hemming and hawing over it. I’ll put it in the Errata. But the fact that there cannot be in the 21st century a defense of white ascendancy is a massive tectonic shift in the culture. Go ahead. |

| S. RODNEY 39:49 | Well, I want actually, to separate out what you are saying and what I’m saying. And I think we’re actually kind of arguing different things. I think I’m saying that part of the anger that gets amplified on social media platforms, digital, social media platforms, it comes from there being something broken in the American ethos. And you’re saying, I think– while acknowledging that, you’re also saying there’s something about that anger that is constitutive of the tribe. That you actually are angry at other people because you recognize them as the enemy, thereby, recognizing people who you identify with as your fellow tribespeople. So– |

| C.T. WEBB 40:38 | Yeah. I mean, that’s basically right. I guess the only thing I would say– and it probably was not clear at all from my tangent, but I’m saying that that anger has become free-floating and detached from its justifiable, easily identifiable target. And that since you no longer have at the center of the culture, at least that people can express in an unapologetic or unconcealed way, white ascendancy. I’ll stop appending all the other adjectives, because there is no space for that anymore. And that anger has become detached. So if you’re at 1955, you are definitely– you can point at white people that have done some fucked up shit to you. If you are living in the South or honestly, in Chicago or anywhere else in the country, it’s not– I mean, let’s get away from the idea that racism was only bad in the South. It’s [crosstalk] ridiculous. It was really– |

| S. RODNEY 41:44 | No, it is. Yeah, we know that. |

| C.T. WEBB 41:46 | –bad in California. I mean, so that absolutely– you knew. You were in contact with them, but we’ve talked about this before. In the last podcast, you sort of [inaudible]. Those stories are becoming more attenuated. The unbridled racism, subjection of your body because you are not a white body. Those stories are becoming fewer. I’m not saying they don’t exist. I’m not saying that there aren’t still too many of them. And that anger and that rage has detached from the actual historical moment and is just sort of free-floating and is used to kind of create these ad hoc communities that are essentially as themselves, as you said, constitutive of the subgroup. The subgroup is defined by its agreements, its outrage agreements. We are angry at the same stuff. We’re mad at the same things. This is how we know who we are. You’re not mad at this stuff. You are therefore fill in the blank. |

| S. RODNEY 42:58 | Right, right. A cock. |

| C.T. WEBB 43:00 | Yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. |

| S. RODNEY 43:03 | Isn’t that a disgusting word? Jesus– |

| C.T. WEBB 43:05 | Yeah. It’s really– |

| S. RODNEY 43:07 | It’s revolting, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 43:08 | Swap out a vowel though, and it’s a good word. I’m just kidding [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY 43:12 | What is? |

| C.T. WEBB 43:12 | I said, swap out a vowel, and it’s a good word. But I was kidding– |

| S. RODNEY 43:15 | It’s not [crosstalk] [laughter]. Yeah, I don’t know that we’ve actually gotten to a place, and I was hoping to get to a place where I understood what to do about– |

| C.T. WEBB 43:27 | We just figured out the anger and shit, yeah, I know [laughter]. Right? |

| S. RODNEY 43:30 | Right? Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 43:30 | Me too, of course. |

| S. RODNEY 43:31 | Okay, so this is the magic formula. This is how you stop being angry, yeah. I know that I don’t want to live there. I know that– |

| C.T. WEBB 43:39 | I mean, I can’t say– |

| S. RODNEY 43:40 | I do not want to live in anger. |

| C.T. WEBB 43:41 | Yeah. I mean, and certainly being conscientious of kind of where the– I mean, the discussion– it’s not really an argument. The discussion’s kind of has run aground a little bit, which I actually think that’s okay. I mean, this is a massive problem in America right now. I mean, and what do you do with it? I mean, I think I would go back to something that I thought of earlier, and then I’ll actually let you have the last word. Which is then, what do I want? What do you want? What do people that are near and dear to me, that I love, and people that I identify as kind of my intellectual peers– what do we want? We want a world in which there is a quality of opportunity and safety to pursue whatever freaky, bizarre outcome you might want for your one precious life. And that starts with, I would say, something like what the Buddhists call “upaya”, which is skillful means. It’s like, “How do you save the people that don’t know they need to be saved?” Right? |

| C.T. WEBB 44:56 | So in that instance, you’re confronted with these very angry activists. And you’re angry, and I’m sure if I was there, I’d be even more angry than you because you have a cooler head than I do. But if it was my best version of myself, I would want to try to respond to them in such a way that allowed us to have a human encounter, to have a conversation. Even if we parted ways, not agreeing at all, and identifying ourselves as occupying different spaces or different wants, that I left feeling like I had connected with another human being. I think that’s what we do. Now how we do that, I don’t know, but I’ll let you have the last word. |

| S. RODNEY 45:42 | Well, I have speculative idea, which is that– and I don’t want to say this in a way that sounds all self-righteous, but perhaps calling things by their right names. I do think it’s important in that moment when people’s [inaudible] are up, and they’re not sure that they can continue being human beings with each other, that everyone in the room, anyone who’s so empowered, call that out and say, “We’re angry right now.” What we’re doing is we’re walking up to the lip of the precipice where angriness is preventing us from actually seeing each other. So not to say that that’s going to sort of dissolve the anger, but to acknowledge it and to say that, “Yes, we’re here, and this is what we have to deal with.” And then, like the characters in the play by Ionesco, I think it is. No, well, no. Is it “Waiting for Godot”? “Waiting for Godot”? The ones who say to themselves– I don’t remember their names, but they say to– at some point, one says to the other, “Shall we go? Shall we make a try?” and just say that to each other. “Can we go? Can we make a try?” |

| C.T. WEBB 47:17 | We can go, and we can make a try. [music] |

| S. RODNEY 47:22 | Yes. I appreciate it. |

| C.T. WEBB 47:24 | Seph, thanks very much for the conversation, and I’ll speak to you next week. [music] |

| S. RODNEY 47:29 | Take care. |

| C.T. WEBB 47:30 | Bye-bye. [music] |

| S. RODNEY 47:32 | Bye. [music] |

References

First referenced at 24:53

Derrida: A Very Short Introduction

First referenced at 26:14

The Sublime Object of Ideology (The Essential Zizek)

“Slavoj Žižek, the maverick philosopher, author of over 30 books, acclaimed as the “Elvis of cultural theory”, and today’s most controversial public intellectual. His work traverses the fields of philosophy, psychoanalysis, theology, history and political theory, taking in film, popular culture, literature and jokes—all to provide acute analyses of the complexities of contemporary ideology as well as a serious and sophisticated philosophy.” Purchase through Amazon here.

First referenced at 28:41

“Poetry. Can identity be pliant and penetrable? Can the speech act be one of attention over intention, can play and fluidity open onto an ethic? THIS ISA NICE NEIGHBORHOOD, Farid Matuk’s first full-length collection, says yes. Yes to the rejection of any opposition between politics and aesthetics, between rhetoric and poetics. Yes to vulnerability. Yes to a poetry willing to enact the errors, uncertainties, and tangled complexities of our political, sexual, and social lives. Testing both narrative and lyric, Matuk finds desire at the root of each, a root from which, these poems suggest, compassion and permission grow intertwined.” Purchase through Amazon here.

First referenced at 30:41

“This collection amounts to a hymn of praise for all the workers of America. These proletarian heroes, with names like Lonnie, Loo, Sweet Pea, and Packy, work the furnaces, forges, slag heaps, assembly lines, and loading docks at places with unglamorous names like Brass Craft or Feinberg and Breslin’s First-Rate Plumbing and Plating. ” Purchase through Amazon here.

Episode 0101 – Comedy: Patrice O’Neal, Laughing Because It Hurts

Patrice O’Neal died in 2011, but his comedy is still hot. Stories that turn a bitter reality into laughter is this week’s subject. Should there be a limit on what comedians can say for a joke?

Comedy: Maria Bamford, How to Maintain Mental Health

The cliché goes that “laughter is the best medicine,” but the idea’s been around for thousands of years, so it’s probably best to call it “wisdom.” How can comedy help us cope with trauma?

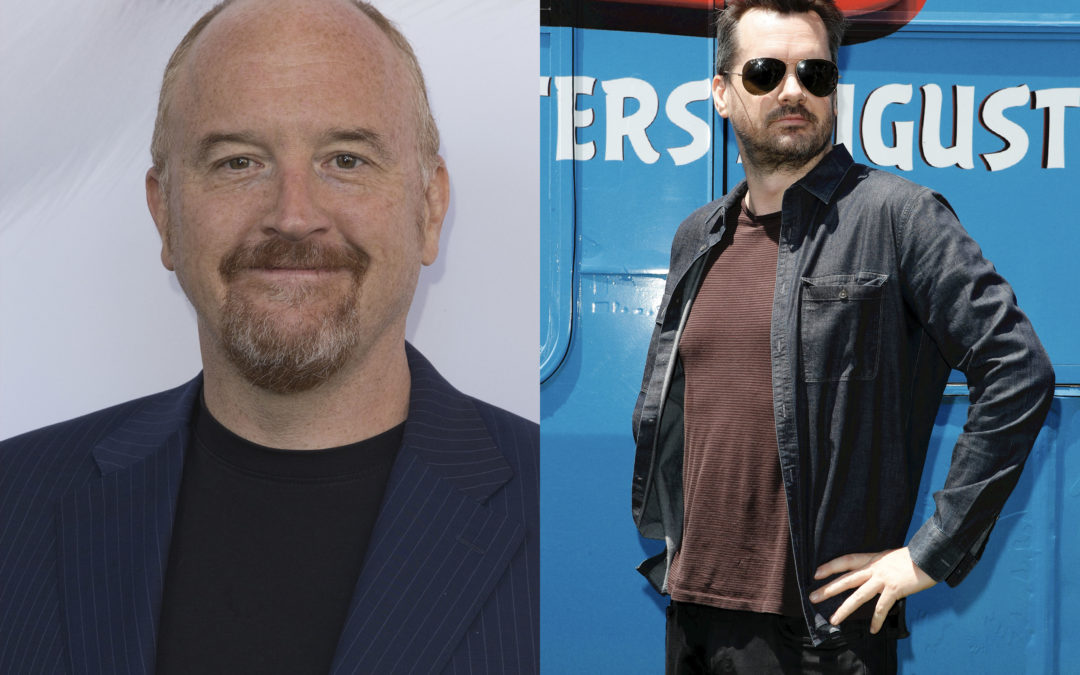

Episode 0098 – Comedy: Offensive Comedy and Its Virtues

There’s laughing at yourself, and then there’s laughing at others. While the former is virtuous the latter is indispensable to group cohesion. In this episode the hosts talk about Jim Jefferies and Louis C.K. What are the limits of comedy?

Humor: What’s so funny?

The hosts take a personal look at what they find funny and why. Fair warning, political sensitivities aren’t off-limits.