0003 | January 16, 2018

Public Outrage: Part I

In this episode, C. Travis Webb and Seph Rodney discuss the coarsening of civic culture. What are the results and causes of public outrage? Are they historical or psychological? (Part I of II)

| C.T. WEBB 00:15 | [music] Good afternoon and welcome to– I should say good afternoon, or good evening, whenever you happen to be listening. Welcome to the American Age Podcast. Today we’re going to be talking about anger. I’m C. Travis Webb and I’m speaking with… |

| S. RODNEY 00:27 | Seph Rodney. |

| C.T. WEBB 00:29 | Who just at that moment was taking a drink, so bad timing on my part [laughter]. So this week’s topic– Seph suggested for reasons that are probably entirely obvious to people that live in the United States, or probably in most developed Western countries. People are really mad about everything. So Seph, why don’t you lead us into that. |

| S. RODNEY 00:55 | I am really interested in public discourse. I think, in some ways, I’ve always been interested in how we talk to each other. Not what we say, necessarily, but how we say it. I don’t think that I would have been able to say this when I was in my 20s. I think when I was in my 30s I began to be more cognizant of this issue being crucial to me. I think part of the reason for that is that I’m actually a rather fragile soul. I think that the ways that people have spoken to me throughout my life, when they’ve treated me with division, or with scorn, or have conversing treated me with honor and with caring. I think that those distinctions are really powerful to me. They have something to do with the way that I feel about my position in the world. They inflect how I feel about where I am and where I belong. |

| C.T. WEBB 02:13 | Yeah, we see ourselves through others, for sure. |

| S. RODNEY 02:15 | Indeed. Indeed. But more than that because I’m so tied to language. And we’ve talked about this over the years, how when I came into a sense of who I am, I really did so through poetry, initially. It was falling in love with Sylvia Plath, and realizing that this woman, who had a life that was almost 180 degrees– 360s a full circle [laughter]. 180 degrees away from me, yet she wrote work that sounded to me like she was speaking my own life. I came into a sense of who I was really through poetry. And Sylvia Plath was one of the key figures in that process. So I’m really tied to language. I’m attuned to it. I’m careful about it, and I value it. And one of the things that I’ve noticed is the level of anger, and vitriol, and scorn, and outright contempt that has colored our public discourse, since I’ve grown up in this states, is worrisome, would be the word I’d use. No, it’s actually more than worrisome. It makes me kind of despair actually. |

| C.T. WEBB 03:49 | Yeah, so I don’t want to veer off topic, and this is not veering off topic, but it does make me think of a conversation I had with a– I think she was a professor of African studies at South– it was in North Carolina at Charlotte. So University of North Carolina. And she was an African-American women, and wore her African-Americanness like a badge. Like sort of traditional African garb and everything. Very with it. Very cool. And she told a story– this is post-election obviously, which I feel like we always sort of reference in absence– we reference the Obama/Trump years. |

| S. RODNEY 04:53 | Because it’s our World War II. |

| C.T. WEBB 04:54 | It is, yes. But for very good reasons. We don’t want– I mean, you and I have kind of discussed this ahead of time not wanting to head down that rabbit hole. But she was expressing her– not dismay, as most of my black Mexican sort of othered friends that I know, weren’t really all that shocked that the election went to Trump. There was the funny Saturday Night Live skit with Dave Chappelle, and sort of as everyone was dismayed at the election results. Anyway, she talked about the difference in expression, and what she was deeply suspicious of is the kind of the racist gentility of someone like a Jeff Sessions, or something like that. Now, whether Sessions is or is not a racist, I’m not really interested in that conversation today. I don’t know him, but so in the way that– and I’ll bring us back to your point, in the way in which people will put forth an argument that’s something along the lines of, “Well, at least I know where Donald Trump stands. At least I know where Jeff Sessions stands. At least I know who David Duke is,” right? Not to say all these people are the same, but you hear this said about them. |

| C.T. WEBB 06:21 | I am so entirely on your side of what I would perceive that argument to be. It actually matters. It matters that we deal with one another in a civil way. And that it actually is demonstrably worse to air your ugliest prejudices in an unfiltered way. It’s not an expression of who you truly are. There is no sort of stable sense– there is no stable self in that way, I don’t believe. But that we are practicing anger. We’re perfecting our anger. We are becoming experts at outrage. And that no, clearly you can mask evil intent with gentility. Clearly you can mask misogyny, and racism, and homophobia with polite language. Of course I’m opposed to that, right? But in civil society, to deal with one another respectfully, cordially, to pay recognition to another person’s life experience, is indispensable to a civil society continuing to endure. And without that, I really think it puts at risk every other aspect of civil society that we depend on. |

| S. RODNEY 08:09 | So what I’m coming to understand right now is that I kind of think we need like two hours to talk about this [laughter], because there are several things that are coming up at the same time that I want to discuss with you. And they’re not– none of them are sort of easy conversations, or quick– |

| C.T. WEBB 08:30 | Okay, so let’s pick one today and we’ll continue next week. |

| S. RODNEY 08:33 | Sounds good. So a couple of things that you said that resonate with me. One is that we perfect anger. I think we actually think that being angry is a kind of strength. And I’m very mindful of something that happened to me last year when I wrote a piece– a really intimate, and actually quite loving piece about an artist named Shaun Leonardo, who– I don’t know that he’s still doing this piece. But he’s a performance artist. So he puts himself live in a space. And he– |

| C.T. WEBB 09:19 | There’s a temporal aspect to his art. So he’s not just like installed somewhere? |

| S. RODNEY 09:23 | Precisely. Precisely. And he’s moving and doing things. And this particular piece that he had devised, he’d done previously, really, deeply, emotionally resonant for me. And important. Basically it was a kind of class on what to do when– if you are a person of color– and this is specifically geared towards people of color, you are snatched up by the police, and they put you in a chokehold. What to do to survive. So literally– |

| C.T. WEBB 09:55 | Oh, man. No shit. |

| S. RODNEY 09:57 | Yes, I think about that and tears are already start to come to my eyes. And he shows how to block a punch, move someone’s arm aside, run away. How when you’re put in a chokehold, to pull the arm down, tuck your chin so that you can get space to breathe, so on and so forth. I want to say– |

| C.T. WEBB 10:19 | That’s actually wrong. You should turn your head to the left or right. |

| S. RODNEY 10:23 | Are you being serious? |

| C.T. WEBB 10:24 | I am completely actually. This is from years– obviously you know my background. But, yeah because it takes– you choke off someone’s– you can knock someone out in about three seconds. So you want to turn your head to the left or right, and you can create space in the crook of the arm by digging your chin into the left or right, as opposed to down, because that is– |

| S. RODNEY 10:41 | No kidding. |

| C.T. WEBB 10:42 | –towards the point of strength. So someone has you in a chokehold, you’re fighting the direct angle of their force by trying to pull down. So you want to turn left or right and dig your chin in. That buys you probably 20 or 30 seconds. |

| S. RODNEY 10:56 | Right. Well, what his point was, I think– and I don’t know where he got the technique from, but his point was you do it in a kind of jerk motion. So that it’s not like you’re fighting it, sort of tooth and nail all the way through. You should jerk the arm down, quickly tuck your chin in, and that gives you at least some time to breathe. |

| C.T. WEBB 11:15 | I buy that. Okay. |

| S. RODNEY 11:15 | So he did the thing, and afterword there was a sort of post-event talk with some activists, who were from the neighborhood. And these people led by an artist I know– |

| C.T. WEBB 11:34 | And by neighborhood, you mean Bel Air [laughter]? |

| S. RODNEY 11:40 | You’re funny. The South Bronx, not too far from where I live. There were three people, and two of them I knew. One an artist I’d known from various things. And one other person that I actually interviewed the year before because she took part in a protest, and they covered [inaudible]. And the third person I didn’t know. But the first person spoke, the artist, and I’m not going to name them because I don’t actually want to reignite that flame more. She, I think, was contemptuous of people in the audience, and I thought the second woman who followed her was even more contemptuous. It was a way in which she spoke. She spoke from this place of anger, and clearly for her she thought that anger was a strength for her. It was a power. It was a tool. And I wrote that they reminded me of supporters of the current president. And that really set them off. They came after me on Facebook, on Twitter. |

| C.T. WEBB 12:44 | Really? |

| S. RODNEY 12:46 | Yeah, yeah, yeah. And they actually pressured Shaun Leonardo to denounce me. Basically he– |

| C.T. WEBB 12:51 | This is the artist? The Shaun Leonardo is the artist? The performance artist? |

| S. RODNEY 12:54 | Yeah, and you should read the piece. I mean, I really do think it’s one of the more feeling pieces I’ve written. |

| C.T. WEBB 13:00 | Everyone should go read the piece, Hyperallergic, Seph Rodney [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY 13:04 | Shaun Leonardo. He even thanked me for the piece, and he said that it was touching and lovely, and he was really moved by it. But after the activist leaned on him, after I said– and I didn’t go into detail about what I thought about them. I said that they reminded me of supporters of the president because they seemed to come from a place of ignorance, and this place of– a pride in their position as outsiders, and their contempt of others, la-la-la. Shaun went on Facebook and said essentially, “Everyone I shared this piece with please take it down. I have to disavow this because I thought that what Seph did was irresponsible.” |

| C.T. WEBB 13:47 | What a bitch. |

| S. RODNEY 13:48 | Yeah, it was awful. And it made me feel really bad, and I had to deal with the stress of all that, while I was actually traveling– |

| C.T. WEBB 13:57 | Shaun Leonardo you’re a coward. You should not have done that. |

| S. RODNEY 14:00 | Well, I mean, I disagreed with him doing that. Where I ended up was, I’m still supportive of his work. I think his work is strong. I don’t like that– but here’s the thing. |

| C.T. WEBB 14:14 | Yeah, let me amend that quickly. The act was cowardly. I, myself, have done cowardly things. So I don’t mean to– |

| S. RODNEY 14:22 | Fair enough. So you want to impugn Shaun? |

| C.T. WEBB 14:24 | Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY 14:24 | Right. Here’s the thing, the anger that they had for me, and we’re ostensibly in the same family. And I get that, members of your own family, you feel more empowered to be angry at. Or to manifest that anger on. And I said this to Shaun actually when we had a phone call, or we exchanged messages somehow. I think I was in Charlotte at the time. Maybe it was email. I said, “They’re so phenomenally angry. Do you not see how this is not working for them?” Because they claim to be representative of the people. Of an underclass. Of an oppressed group. But they’re main tools are not actually social organizational, political organization, or finding ways in to get their agenda accomplished. The main tools are protest. And so I am suspicious of that, and I feel like that moment, that debacle, made me even more aware of how mean spirited, and ill advised, our public discourse tends to be. Because what we want to do, what they wanted to do when they felt insulted and harmed, they didn’t want to reach out to me and have me explain. Or engage me and find a way to have me turn that around. Maybe saying something subsequent, saying maybe I was wrong about this. |

| S. RODNEY 16:01 | What they wanted to do was they wanted to silence me. They wanted to get out the tar and feathers, and set me on fire, and send me out of the town, and out of their sight forever. Like when did this become typical for us? |

| C.T. WEBB 16:20 | So I had another response, but you asked me a direct question, so. When did it become typical for us? Probably there is no moment that it became acceptable to disregard people in civil society, in such a perfunctory way. But I do think that– I mean, one thing we can’t lose– or we shouldn’t lose sight of, in sort of navigating the 21st century America, is how identity was constructed in this country for 200 plus years. There’s a lot of very solid academic work. And I don’t mean sort of fringy cultural theory, but I mean solid historical research. Furstenburg, is In the Name of the Father. I don’t remember his first name, but that identity– like what it meant to be a free American. What it meant to be a free participating member of civil society was to be a white male. |

| C.T. WEBB 17:49 | As you know, in our– I mean, really one of the things I want to try and accomplish with the American Age is finding a way for us to move past those shoals. But we can’t move past them until we’ve come to terms with them. And that dismissal of the other was something that was done easily, and out of hand, for 100s of years in this country. If you didn’t look like me, you weren’t heard. No one gave a shit what you had to say, right? |

| S. RODNEY 18:31 | Right, you weren’t worth listening to. |

| C.T. WEBB 18:32 | Yeah. I mean, there’s the famous– I mean, it’s one of those apocryphal stories I actually– I’ll look it up after we’re done with the podcast and actually put it in the [inaudible] section. But the Native-American needing to prove that he was a human by bringing him before congress and having him cry. So this is one of those anecdotal stories that I’ve heard. |

| S. RODNEY 18:51 | Jesus Christ. Oh, my God. |

| C.T. WEBB 18:53 | So let’s just bracket the truth, the facticity of that. Do you doubt it? I don’t doubt that. |

| S. RODNEY 19:03 | No, no. Not at all. |

| C.T. WEBB 19:05 | It’s one of those things where like, yeah, okay, I believe that definitely there were a bunch of wig wearing crackers that absolutely needed you to come perform your humanity for them, in some sort of perverse [inaudible]. So yeah, I believe that. Now, I’ll look it up and see if it’s accurate or not, and I’m happy to correct the record. But– |

| S. RODNEY 19:31 | But we both agree that the circumstances were such that such an action would not be strange in such a context. Right. |

| C.T. WEBB 19:40 | Right. And so I wonder– I think there’s two ways that we can come at this problem of kind of the state of civil society in America. One is the broader historical story. And two, is sort of the individual story of what brought these two women to express their opinions in this way? What brought this artist to respond in that way? |

| S. RODNEY 20:09 | Please remember what you were going to say, but I need to just– |

| C.T. WEBB 20:15 | No, jump in. |

| S. RODNEY 20:16 | –jump in here and say that it’s important that I’m not just talking about people on the Left. And we do need to do a podcast on what that means. But I’m reminded to of what Dana Loesch did for the NRA, and her ad, that basically said, “People on the Left are all devils. And we need to smash them with the fist of truth.” Which to a reasonable person I think sounded like, “We need to take up arms against these mother fuckers and make sure that we protect our own.” And I looked up the backlash, and apparently online I– rudimental research, apparently– and these are only Right-wings sites that I found this information on. Dana Loesch was supposedly forced to move because there was so much Left-wing anger against what she said. Now, mind you, what she said was essentially an incitement to war. And basically it said to all the gun owning NRA supporters, these people are trying to take your country away from you. So what are you– you going to man up, or what? |

| C.T. WEBB 21:30 | Okay, so– |

| S. RODNEY 21:32 | Go ahead. |

| C.T. WEBB 21:32 | –that actually fits in with what I was going to say. So there’s two ways to look at it all– I mean, there’s probably more than two. There’s two sort of broad strokes that we can come at this issue of moral indignation on the Left. We’re talking about the Left right now. Yeah, there’s moral indignation on the Right, and there’s probably a different answer to that. But that is sort of the broad sweep of history. And so you have a bunch of non-white men and women, really non-white women. I mean, if you want to talk about a class, or a group of people, that really have been ignored in American history, black women, Mexican women, I mean, this is just not– |

| S. RODNEY 22:14 | Systematically. |

| C.T. WEBB 22:15 | Yeah, yeah. Not strongly represented. So if you want to read the moment as historical comeuppance, right? So this sort of social forces are breaking free from the white patriarchy. That narrative makes sense. I don’t agree with that, right? I actually think there’s a lot of problems with that argument. But we have to acknowledge that it’s a plausible story. That’s a plausible story for why people are so upset about the state of the world. And then the other side of that is we can come at these stories as, what is this person’s particular background? How much have they actually suffered? How are– |

| S. RODNEY 23:11 | Which is a contentious argument. |

| C.T. WEBB 23:13 | –they placing– what sort of guilt do they have in their own life [laughter], in the construction of their own identity? They weren’t marching in Selma, right? They aren’t on those buses. But yet they want to own that red badge of courage. |

| S. RODNEY 23:34 | Right. Let me paint the other side then. So the other side is essentially the free-market, flag waving Christian, America first, nationalists, kind of conservative who basically looks at the world as– the social world as a place of contest. And I suspect that |

| why– so we do need to talk about the technological innovation of the internet, because I think– and Glenn Greenwald’s argument in the piece that I sent to you, which is titled The Petulant Entitlement Syndrome of Journalist, gets into this, is also a thing. But to stick with what I’m talking about, I think there’s a kind of– maybe I shouldn’t quote that. Yeah, it doesn’t need quotes. There’s a white-settler mentality I think that colors the conservative viewpoint in the US, which is that the social world is a place of contest. And if you are not winning, you are losing, which is why– part of the reason that Trump is so resonant with these people, because that world view does have traction for them, right? | |

| S. RODNEY 25:00 | That if you are not winning you are losing. It is a Manichean world. I want to say, that in those terms, if you accept that premise, if you come to that argument. |

| C.T. WEBB 25:17 | Which I got to say, we can– I may be open to that as a metaphysical principal, to be quite honest, but– |

| S. RODNEY 25:27 | That the world really is winning or losing? Are you serious right now? |

| C.T. WEBB 25:30 | No, no. No, no. Not that the entire world is winning or losing, but that– I don’t want to get sidetracked. You finish your point. There is some softness on the Left, and amongst intellectuals that– and I’m not coloring you with that brush, but I’m saying that argument. There is, at the heart of cultural engagement, contestation, conflict, agon. |

| S. RODNEY 26:16 | Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB 26:17 | Struggle. |

| S. RODNEY 26:17 | Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB 26:18 | A [crosstalk]. I mean– |

| S. RODNEY 26:20 | Yes, but it can be productive as opposed to be– |

| C.T. WEBB 26:23 | Oh, absolutely I think it can be productive. I want to kick their ass. This is nothing like– I want to win. I want to defeat their bullshit arguments. But I actually feel that way. |

| S. RODNEY 26:36 | Right, no I feel you and I do to. But my point in the way that I am describing the conservative outlook, is that there is no other outcome possible. Whereas, I think– and you know this from being married, I think, and I know this from being in relationships that have been deep and long, that there is contest in them. But what falls out is not necessarily just winning and losing. What falls out sometimes, is just knowledge of the other and of yourself. |

| C.T. WEBB 27:12 | Yeah, so from a certain point of view– I mean, you can sort of– you can kind of engage at these things at multiple levels, right? So I’m with that. In defeat there can be wisdom, and whatever. Whatever sort of Yoda thing you want to throw at it. |

| S. RODNEY 27:29 | But I don’t necessarily think it has to even be colored as defeat. It’s just a thing. Like you lose an argument, you lose an argument, you recognize that the other person has a valid position. And you say, “Yes, I recognize that.” Is that losing? |

| C.T. WEBB 27:43 | Not in the way that you just characterized it. But I do think that in the field of cultural politics, and in the field of history, it is not a mistake to see certain ideologies as an incompatible. |

| S. RODNEY 28:13 | I agree. I agree with that. |

| C.T. WEBB 28:14 | I think, for example, along these lines, and let’s tether it kind of closely to sort of the outrage that prompted this discussion, what you experienced and the response to that. If you believe, if you operate from a racial framework as a valid epistemological, and moral framework, to organize human beings, you are absolutely under attack in the 21st century. |

| S. RODNEY 28:53 | Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB 28:53 | If you believe– if that is your ideology, you are losing. You may not– I mean, economically, sure, okay. Most professors, Fortune 500 companies, all that kind of stuff, but just like the canary can tell you that you’re in trouble before your lungs tell you that you’re in trouble. The direction of the culture in the Western world tells white men, in particular, that they are in trouble. |

| S. RODNEY 29:27 | Yes, and I agree with that. |

| C.T. WEBB 29:28 | That privileged position is under threat. If you operate in the world with that framework, you are losing. And you are correct, you are losing and here’s why. Because it’s a bullshit ideology. It’s wrong. |

| S. RODNEY 29:48 | Right, but more than that. More than the fact that it’s a bullshit ideology because we live with a lot of other bullshit [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB 29:54 | Fair enough. |

| S. RODNEY 29:55 | But part of what’s happened in– and I think it’s a 20– right, in the 20th century, is enough people that come together. And I said this actually at a– well, a gettogether. I was about to say party. It really wasn’t a party, it was a gettogether at Steven Fullwood’s house, a friend of mine who works at the Schomburg Center, or worked at the Schomburg Center. He’s now retired from it. I said that one of the things that I think are hallmark’s of human progress, let’s call it, was the moment when the UN– and I don’t remember exactly what year this is, but the moment when the UN came up with– developed a rights of man, or rights of people. |

| C.T. WEBB 30:42 | Are you talking about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights? |

| S. RODNEY 30:46 | Thank you. Thank you, that was it. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. What they did in that moment, was they articulated a sense of principals, which said, outside of any religious– an inherited immoral scheme, that simply by being a human being, you deserve a certain kind of recognition, and a certain form of respect. That’s astonishing. |

| C.T. WEBB 31:19 | Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 31:20 | Right? What we basically said to each other was, “No, no, no, no. You’re here now. You deserve at least this [inaudible] of what we can provide you so that your life isn’t complete shit. You deserve to have the autonomy of your body.” That’s huge. That’s’ huge. To say that to a child, who’s married off at 13, “You deserve to have the autonomy of your– you deserve to have the agency to make choices about what you do with your body.” That’s astonishing, right? And I agree. I think it’s a bullshit ideology, but I would go farther to say that things like the universal recognition of a kind of value in humanity, has made it less possible for white men to simply say, “Oh, that’s a shithole country.” Right? |

| C.T. WEBB 32:18 | Right, right. |

| S. RODNEY 32:19 | Like those people don’t deserve our countenance. Our care, yeah. So I really do feel like we need to pick this up next week because there’s so much more to say. |

| C.T. WEBB 32:36 | Well, I think we can squeeze a few more minutes in. Maybe 10 [laughter]. So in 1948 was the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and so you know that this is something that’s near and dear to my heart. I mean, this is where I think the Left has gone off the rails a little bit. This was an actual social advancement. This was something– I buy, I own Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I would enshrine it above every religious codicil. I would put it above every– |

| S. RODNEY 33:20 | Amen. Amen. |

| C.T. WEBB 33:21 | –national declaration of what people should, or shouldn’t be entitled to. So I’m 100% onboard with it. I’m all in on it. And to bring it back to the anecdote that you opened this up with, one of the things that seems to be missing in civil discourse right now, in the United States, is that the belief that decades, centuries of iniquity, means that you don’t have to play by those rules. That because white history in America, and in the West, more broadly, produced such an awful, terrible, heinous history for non-white peoples in Europe, that therefore it’s their turn. It’s their turn to get kicked. It’s their turn to be shouted down. It’s their turn to be silenced. And that is the exact wrong lesson to take. It’s the wrong way to go. |

| S. RODNEY 34:36 | Exactly, because all you do is perpetuate the system of domination. You say that if you are in power, than it’s fine to put your boot on the neck of whoever, blah blah blah. Yeah, it’s a shitty response. It’s a myopic one. It’s one that basically says, “I really don’t care about what happens to the future. I just can’t watch it in front of me.” What I can see. What I can touch, and feel, and manipulate. It’s a mistake. I agree with that. But here’s something I want to get to, and I want to relay this anecdote, with the understanding that we may need pick this up after– what, eight minutes left, are done. It’s something I heard from This American Life, and it really helped me make sense of a lot of things in my own life. It was several years ago, it was an episode that had to do with couples relationships. The premise of their episode, or the precede was that they wanted to look at what caused relationships to end. And it wasn’t, they found, and they leaned on a particular study that was carried out by– |

| C.T. WEBB 36:01 | I know what– please continue. I actually know exactly which one you’re talking about, but please continue. |

| S. RODNEY 36:05 | Right, they’re a couple sociologists, right, who looked at several couples. Gay, straight, different ages, blah blah blah. Basically looked at the way they argued, right? And they could predict whether the relationship was going to last– I’m glad that you know this. It’s nice that you’re nodding along because it was so profound to me to learn this. That the precise predictor of whether or not the relationship would last, was whether, when they were arguing, they treated each other with contempt. |

| C.T. WEBB 36:45 | How they fought. |

| S. RODNEY 36:46 | So let’s be clear– right. How they fought. So I’m concerned with how we talk, how– it’s actually how we fight, right? How we carry it out, right? So let’s be clear about of what contempt means in this case. Contempt, I think, I don’t remember the essay– sorry, the episode, well enough to recall what they described it as. From what I understand, contempt is the articulation of a position that the person you are talking to or dealing with, is not worth your consideration. That what they’re feeling, what they’re thinking, does not ultimately matter because you are so disgusted by them, and their presence, what they offer, that it’s not worth taking onboard at all. Would you agree with that? |

| C.T. WEBB 37:35 | Yes, absolutely. I mean, I think what you’re describing is precisely– I mean, in an intimate setting, is precisely what you experienced at that talk, or as a result of that talk. That– |

| S. RODNEY 37:47 | Right, it’s contempt. Right. |

| C.T. WEBB 37:49 | Yeah, what you have to say is so beyond the pale, that you don’t need to be heard. And, yeah. And on the other side of treating one another this way, is chaos. I mean, that’s what a relationship that’s– I mean, anyone that’s been involved in a failing relationship, it’s chaos, is what it is. I mean, I suppose– you’re failing relationships, you’re not really connected, or invested, or whatever and you kind of exit easily. But for anyone that’s been in an invested relationship that is ending, those days, those months, those moments, they’re chaotic. |

| S. RODNEY 38:39 | Excruciating, and awful. Sorry, go ahead. |

| C.T. WEBB 38:44 | No, no, no. Please. No, go ahead. |

| S. RODNEY 38:46 | I just remember a relationship ending with one woman I loved deeply, Jennifer. And we had gotten to the point where we just– the fights would just sort of breakdown into– just one of us leaving the room. And I left this time, and I got into my car, which is parked underneath the living room window, in the back of the apartment we shared, and I remember getting into the car to just drive away. And she opened the window and she started throwing the books in the library at me from the window. Like that level of chaos. That level of, “I don’t know what to do anymore,” right? |

| C.T. WEBB 39:27 | Right. It reminds me– the thing that it made me think about when you were describing what leads to the breakdown in relationships, and then what you experienced as a result of your position, your critique of that engagement with the art piece, is the WH Auden poem, “September 1st, 1939,” when he says, “I, and the public, know what all schoolchildren learn. Those to who evil has done, do evil in return.” And I mean, we sometimes forget the really basic simple truths of being human together on the planet, as if any of us have any fucking clue, like where we’re going, or what’s happening, or what led us here. |

| S. RODNEY 40:27 | Or even who we are in all of that mischigas, right |

| C.T. WEBB 40:31 | Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 40:31 | And all that craziness? |

| C.T. WEBB 40:33 | Yeah, absolutely. So why don’t we pick this up again next week, and we can– I mean, it’s certainly a fruitful area of discussion, anger and what we can do about it as a society, as a culture, right now in the 21st century, 2018. |

| S. RODNEY 40:53 | Yeah, I think it’s an important conversation for us to have. And I think we need to bring in people like Glenn Greenwald and what he suggests, which is essentially that the onset of the internet has actually allowed public opinion to proliferate in a way that it had not, it actually allows us to hold elite’s feet to the fire. And I’m not sure if that’s a solution. I’m not sure that he’s putting it forward as a solution, but I think we do need to talk about that, and sort of the breakdown of elitism versus a kind of populism. |

| C.T. WEBB 41:29 | All right. So social media’s role in the antagonism between elitism and populism, and we can pick that up next week. |

| S. RODNEY 41:35 | Amen. Amen. |

| C.T. WEBB 41:37 | All right my friend. Okay, I’ll talk to you next week. |

| S. RODNEY 41:38 | Okay, take care. |

| C.T. WEBB 41:40 | Bye-bye. [music] |

References

No references for Podcast 0003

Episode 0101 – Comedy: Patrice O’Neal, Laughing Because It Hurts

Patrice O’Neal died in 2011, but his comedy is still hot. Stories that turn a bitter reality into laughter is this week’s subject. Should there be a limit on what comedians can say for a joke?

Comedy: Maria Bamford, How to Maintain Mental Health

The cliché goes that “laughter is the best medicine,” but the idea’s been around for thousands of years, so it’s probably best to call it “wisdom.” How can comedy help us cope with trauma?

Episode 0098 – Comedy: Offensive Comedy and Its Virtues

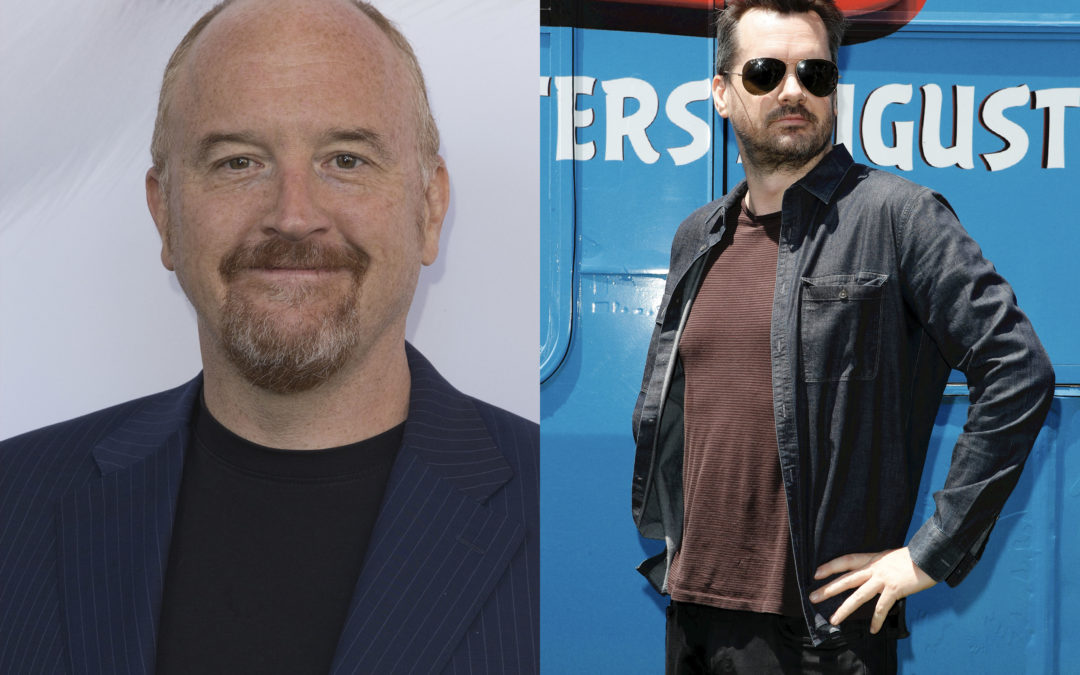

There’s laughing at yourself, and then there’s laughing at others. While the former is virtuous the latter is indispensable to group cohesion. In this episode the hosts talk about Jim Jefferies and Louis C.K. What are the limits of comedy?

Humor: What’s so funny?

The hosts take a personal look at what they find funny and why. Fair warning, political sensitivities aren’t off-limits.