0063 | March 18, 2019

White Misanthropy: How to Stop Being “White” and Start Being “Human”

In what ways does “white” ideology interfere with human empathy and compassion? And what does it mean to be “human” anyway? Can a better version of the United States be written in the twenty-first century? The hosts draw together several threads from their previous podcasts.

| C.T. WEBB: 00:19 | [music] Good afternoon, good morning, or good evening, and welcome to the American Age podcast. My name is C. Travis Webb, editor of the American Age, and I am joined by my wonderful friends who will now introduce themselves [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 00:32 | I’m Seph Rodney. I’m an editor of Hyperallergic, the online arts magazine and a member of a part-time faculty at Parson School of Design. I have a book coming out in June, and I’m actually in the middle of copy edits on it. So– |

| C.T. WEBB: 00:51 | Did you finish yesterday? |

| S. RODNEY: 00:52 | — [inaudible] in my head. What? |

| C.T. WEBB: 00:53 | Did you finish yesterday? You were saying– I know you were looking at the [inaudible] yesterday. |

| S. RODNEY: 00:55 | Oh, I kind of finished at like four in the morning, but “kind of,” I say because there’s one small chapter I have to look over and then the references and then I can send that off in– I don’t know– a couple of hours. |

| C.T. WEBB: 01:07 | All right, all right. Yeah. Knock, knock, congratulations. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 01:11 | Congratulations, yeah. That’s dope. |

| S. RODNEY: 01:12 | Thank you, [inaudible]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 01:14 | I’m Steven G. Fullwood, and I am one of the co-founders of the Nomadic Archivist Project, and it is an archival, consulting company. And we look at individuals and organizations who want to do something with their archives specifically. And next week, I will be in Philadelphia at the William Way Center talking about community archives with some amazing people. So if you can, it’s a public event. Again, it’s March 13th. Well, actually, not again. This is the first time I’ve mentioned it. March 13th, and it begins, I believe, at 11 o’clock. |

| S. RODNEY: 01:48 | Nice, nice, nice. |

| C.T. WEBB: 01:49 | And, Seph, you’re going to be in the Netherlands next week, is that right? |

| S. RODNEY: 01:51 | Yeah, that’s right. I’m going to cover the TEFAF-Maastricht Fair. So I will be flying out on Tuesday night, and then I’ll be there from Wednesday through Sunday. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:02 | Awesome. Have a great trip. |

| S. RODNEY: 02:04 | Thank you. |

| C.T. WEBB: 02:06 | So this is to remind our listeners that we practice a form of what we call intellectual intimacy, which is giving each other the space and time to figure out things out loud with one another and sometimes get into it a little bit, which is productive for me I know. So we’re going to continue our conversation from last week. There will be less talking between Steven and I [laughter], and we’ll let Seph– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:25 | Maybe. We’ll see [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 02:28 | We’ll let Seph take the lead on this one. So, Seph, do you want to lead us into it? |

| S. RODNEY: 02:33 | Well, I think that last episode, we didn’t get as much of a chance to answer Steven’s initial question as I wanted to. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:46 | Okay. |

| S. RODNEY: 02:47 | Steven’s question was, essentially, instead of talking about how white misanthropy ends up victimizing, hurting people of color, that we should take a really close look at how it ends up hurting themselves, how it ends up hurting whites. And he gave us several things to look at. And one of the things that– and I’m looking it up right now actually– was an interview of Toni Morrison on Charlie Rose. And an article called, “10 Ways White Supremacy Wounds White People,” and another article– I think this one in The New York Times, “How Can I Cure my White Guilt?” and the last was the essay by James Baldwin titled, “Here Be Dragons.” So I looked through all of these, and there were essentially three things I came up with to answer that question. One was– and I think this is from “The 10 Ways White Supremacy Wounds White People” piece– was that whites end up revering thinking over feeling, which puts them at a disadvantage because then they don’t know what their feelings are in particular instances when knowing what your feelings are is really important like when you go to a– and, actually, wow, I just thought of this moment in David Foster Wallace’s essay, and I don’t remember the name of the essay, but he talks about being at the fair. And he talks about– oh, wow– you know what, no, I’m conflating it with something else. I’m sorry. No, it wasn’t David Foster Wallace. It’s someone else. But he talks about being a fair and painting children’s faces, and a couple coming through with a young boy, and the boy wanting some “girly” color like yellow or pink. He just gravitated towards that, those colors. And she started to paint his face, and the wife looks down at him and her, at the woman painting the boy’s face, and angrily screams at her, “Don’t do that. He wants boy colors! He wants blue! He wants purple [laughter]!” And she said that the woman– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 04:59 | Purple’s not a boy color. |

| S. RODNEY: 05:00 | Okay, fair enough [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 05:02 | I was joking. |

| S. RODNEY: 05:03 | No, I know that. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 05:03 | It was a joke, it was a joke [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 05:04 | I know. I know. But the mother was so incensed that the boy– her son, more to the point– would choose a color that wasn’t in-line with their idea of masculinity [laughter], that her anger boiled up and over in a situation where that just was not called for. So there’s that. So the revering of thinking over feeling in such a way that one doesn’t necessarily even have access to one’s feelings in moments when it’s important to. In that moment, the mother really needed to know what she was feeling was fear, right? Fear that her son might be queer, that her son might not be hetero-normative in a way that she needed him to feel, in a way that would affirm her own life, right? The second one is white misanthropy ends up dividing this world into a kind of Manichean scheme of winners and losers. And we all know– at least everyone within the sound of our voices should know that that kind of arbitrary divvying up of the world makes no sense. If you divvy up the world into winners and losers, you negate, I don’t know how much, what percentage of human experience there is, by not allowing yourself to be open to it. A sunset is not a win or a loss, right? Being curious and looking up a word in an online encyclopedia is not a winning situation or a losing situation. Being in love is both and neither winning and losing. Being humiliated and learning a lesson that one then takes to find success in another area of one’s life. It’s both winning and losing. |

| S. RODNEY: 07:12 | I mean, it’s just– it’s a kind of silly-ass thinking that impoverishes us intellectually, and this kind of thinking is absolutely encouraged by white misanthropy. And then there’s the last one, which I got from reading Baldwin’s “Here Be Dragons.” And this one– this is powerful for me. At the bottom of the first page of the essay, he says, “All countries or groups,” and I’m quoting here,” All countries or groups make of their trials a legend or, as in the case of Europe, a dubious romance called ‘history.’ But no country has ever made so successful and glamorous a romance out of genocide and slavery.” And this is the thing about white misanthropy that is truly dangerous is that if you make that romance, right– and we can think of films that are representative of that kind of romance, Gone with the Wind, but of a nation that makes a romance out of genocide, out of the conscientious killing, elimination of a group of people who are different from you essentially because they are different, and you’re competing for resources. And slavery, the rendering of human beings into property and the resulting systems of violence and exile– of political and social exile that are meant to keep them in that position, all those things, it seems to me, work against people who wield white misanthropy because that lie permits you to lie about everything else. |

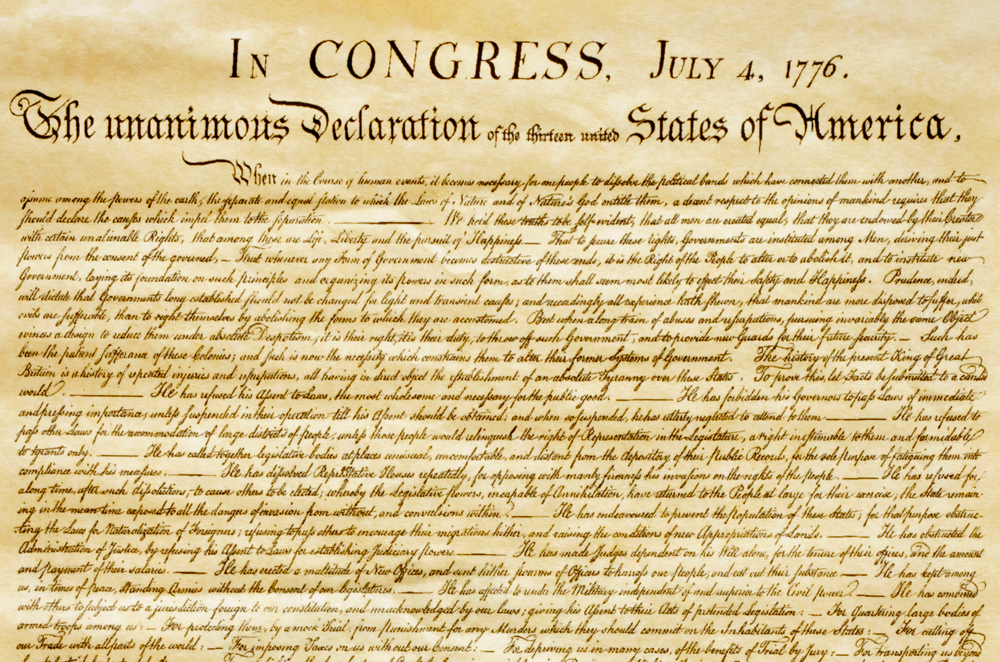

| S. RODNEY: 09:04 | I think that if you can lie to yourself enough to say, “The US is built on the backs of these really honorable, independent thinkers who penned the Declaration of Independence has nothing to do with genocide and slavery.” If you can tell yourself that lie, what other lies are you telling yourself? Is it even possible to live your life with any sort of integrity if you can’t recognize the basic lie of your own nation’s history? Those are the three ways, I think, that misanthropy really hurt and hinder whites who wield that ideology. But I have a question– I have a question because ultimately, at the end of this, there’s this kind of– at the bottom of all this, there’s this kind of vague, I think, notion of what our humanity’s supposed to be, right? Because all of these things, essentially, as someone said in one of those articles– I think it’s “10 Ways White Supremacy” well, I don’t remember the name of the article, but I mentioned it before– the writer ends up saying, “We end up trading in humanity for the illusion of comfort.” |

| C.T. WEBB: 10:30 | Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 10:31 | Right. But my question is, “What is humanity?” Because at the bottom of all these things, right, I’m essentially saying there is a kind of notion of what a human being should be, that revering thinking over feeling, devolving of– imaging a world that is Manichean, that’s only winners and losers, and that’s built upon the lie of the nation-state consisting of a romance instead of actually the horrors of genocide and slavery. All these things are premised upon this idea, I think, that I’m holding of what humanity should be. What is that humanity? What am I trying to evoke here? Because I’m not sure. |

| C.T. WEBB: 11:25 | So I don’t know that I can directly answer your last question. I think I probably can give you what I would like it to be. I would like to qualify Baldwin who I love, and it’s just not true that we are the only example of a large community of strangers that has tried to put shine on shit. |

| S. RODNEY: 11:56 | No, no, no. No, no. I want to be clear here, though. He said that– |

| C.T. WEBB: 12:00 | Or even the best. |

| S. RODNEY: 12:01 | Okay, okay, so that’s your argument then. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 12:03 | “Ever so successfully.” |

| S. RODNEY: 12:04 | Right, that’s his point. |

| C.T. WEBB: 12:06 | That’s just a narrow– that’s a narrow arc of time. We’re the future’s trash. We’re some future archaeologist’s remainder, and certainly, during its time, Mesopotamia was just as successful, and the early Chinese dynasties were just as successful. There’s plenty of murder and deprivation and slavery to go around. |

| S. RODNEY: 12:35 | Fair enough. |

| C.T. WEBB: 12:36 | I don’t say that as a defense of the United States [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 12:39 | No, no. No, I get it. |

| C.T. WEBB: 12:41 | And, in fact, I think what I probably– the only small thing I would like to tweak with Baldwin is– I don’t know that– and maybe this is actually what he was thinking because he is such a nuanced writer and thinker– the intensity of the hypocrisy of the United States and the contrast of its soaring rhetoric versus its actual historical practices, that may be unequaled. I mean, the idea that all men– this idea, “All men are created equal, yadda, yadda–“ |

| S. FULLWOOD: 13:12 | Oh, yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 13:13 | Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 13:14 | — at the same time that we were doing the things that we were doing. I might go in that that has never been equaled. I would say, for me, the humanity thing is– to me, the defining characteristic of being human is the ability to– not language, not art, none of this stuff– but is the ability to cooperate with strangers. The ability to– the capacity to do that. I think that is when we are at our best, that we can see people that we do not know, that are not a part of our tribe, that do not contribute in any utilitarian way to our everyday existence or survival, and we can still try and lend a hand. To me, that is the best version of ourselves that we regularly fall short of. |

| S. RODNEY: 14:10 | Regularly. Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:13 | But for me, that would be an answer to your question. That would be what– the better version of the world that I would want to work towards is a world that regularly cooperates to help those who are strange to them. |

| S. RODNEY: 14:31 | And I want to ask Steven to jump in and to answer the question, but I want to just quickly follow-up, Travis. Are you saying, basically– you’re looking at this sort of faculty of being unselfish, an ability to be unselfish? |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:47 | So I would say not “unselfish” but a more capacious selfishness so that the self is encompassed to be far larger than whatever your sort of narrow circle of concerns are. That “Ask not for whom the bell tolls,” right? The John Donne poem. That would be the better version, for me. |

| S. RODNEY: 15:15 | Okay, that’s lovely. That’s really beautiful. Okay. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 15:19 | Okay. So following up on what Travis said, being able to cooperate with strangers. So on my door– every day before I leave, on my door on an index card, it says, “Everyone’s needs matter.” And I was thinking about why I wrote that. And I wrote it because I was thinking– I think I was going through something last year where– you know how you’ll have a bad day, and then you get more bad news from other people, and then you’re trying to figure out how much to commiserate [laughter]? How much to let your own self go? Or how can you just be there selflessly or less selfishly and listen to someone else, and say, “Okay, why don’t you come over for dinner?” or, “Why don’t we talk it out?” and you don’t really put your own thing in there to make it more palatable for you or more worth your time. And so I wrote that down because I always want to remember that no matter if I’m aware of the reason for the need [laughter] or the rationale for the need, that they matter, right? And I love the idea of living one’s full humanity, and I think that what Travis is– this idea of cooperating with strangers, it just feels right. It feels like one of the things that connects me to everybody as we’re one thing trying to be with each other and learning how to be with each other, and that we do fall short of it. And I think we’re afraid of it because it makes us vulnerable, it makes us open. If that could happen to that person, that means it could happen to me. But as long as I keep a wall up or I keep some sort of barrier up, then I can say, “The reason why Travis or Seph is in this position is because they did A, B, and C. I’ll never do A, B, and C, and therefore, I can’t connect with that experience.” You can connect with– the most funny thing recently– not funny, but the Leaving Neverland. How people have been asking people about how they feel about it, and one of the common things I’ve been getting is, “I can’t watch that right now.” |

| S. RODNEY: 17:27 | Whoa. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 17:29 | And my theory is, based on the person is, then you have to think about, “What does it mean in your life? Will you cancel Michael Jackson? Do you believe the kids or not? Will you blame them?” It will require you to be a human in a very uncomfortable way. And I think that uncomfortableness really feeds into cooperating with strangers. It’s not convenient. It’s not convenient, but I think it makes you a more thoughtful person, maybe a more introspective person. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:57 | Yeah, it takes a tremendous amount of resources, emotional resources to extend your circle of sympathies that large. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:04 | Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:06 | And maybe many of us don’t have the bandwidth to do that for a variety of reasons, that again, I would not be judgmental about; working two jobs or just aren’t really built that way, have a hard time handling their own shit. For me, the whiteness thing, and you gave a– some of those things to me are not unique to whiteness. And we don’t have to talk about that– I don’t know if that’s a productive conversation, but what I do think for me at least to add to that is that where whiteness slots into what we’re talking about now is that whiteness is that differentiating element that leads people to believe that they are different from, uniquely essentially different from one another. And anytime you introduce that kind of overarching element of being the chosen ones, then you are impeding the ability to sympathize and extend natural human sympathies to others– or what I would consider natural human sympathies. And now, there are better versions of that being special. For a long time, in Judaism, the idea of the Tzadik, so the righteous ones. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:26 | Right. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:27 | So that the Jews are the chosen people, but the best of them hold up the world with righteousness. Now, that’s not a bad story. That’s a pretty decent one, right? Not that it can’t be misused, but– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:37 | Mm-hmm. Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:38 | But that that story’s pretty– that you feel that your biology sets you apart to be some sort of better inheritor of civilization and civilization’s story, that’s not going to make you ever a better person [laughter]. It’s just not ever– that’s never going to result in a better human being at the end of that story. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:01 | Right. At the end of the story, but we presume that people want to be better. |

| C.T. WEBB: 20:06 | Yeah, fair enough. That’s true [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:09 | Over and over again. That’s one of my things that I always catch myself going to do that work, the emotional resources, the bandwidth, all of that, it’s building the capacity to do that, right? You’re not born with it. Maybe. Maybe, maybe not. But just caring about other people selflessly requires me to be less Steven-focused. Mm-hmm? |

| S. RODNEY: 20:33 | Sorry to interrupt, Steven. I just want to give an anecdote. I love putting actual real, lived circumstances to the kind of abstract things we get onto. And I remember there was a moment when I was doing my graduate degree, my MFA at UC Irvine. That’s when Travis and I got to know each other, I think right after I graduated. |

| C.T. WEBB: 21:02 | Yeah, that sounds right. |

| S. RODNEY: 21:04 | I remember there was a– let me actually preface this by saying, up until the point where I was working on the PhD, the MFA was the hardest thing that I’ve ever done in my life. I didn’t know that the work would be that hard. It was classes all day. It was TA’ing. And then it was trying to find time in my studio to make work– make work for me and make work for the program. And there was a moment when I was exhausted. I had been running around all day, and it was a class that got let out at 5:30 or 6:00 or something. And I was just really looking forward to going to my studio and just closing the door and being by myself for a minute, and a student came up to me and asked me something about a paper that I’d graded or something that I’d written on her paper. And I remember her talking to me and looking at her and thinking, “I’m exhausted. I just really do not want to deal with this. I just really want this person to go away.” And I’m not sure why, I’m not sure how, but I found something in myself, I found a deeper place, I found another gear, and I opened myself up to her, and I listened, and I solved it. And I remember thinking in that moment, “I did not know that I could do that.” Everything in me was saying, “Just tell her ‘another time.’ Walk away. Do something else.” But I found it. I found it in myself to do that. And I remember that moment staying– it has stayed with me since it happened more than 18 years ago, and I think about that a lot because there are a lot of times when I don’t do that. There’s a lot of times where I do just walk away. And I keep thinking, “But fuck it, man, I have the capacity. I can. If I dug, I could find it in myself to do this for this person.” And I’m not saying that I don’t always, and I’m not saying that I do always. It’s just when I don’t, I look at myself, and I think, “But, Seph, you can do this,” right? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:22 | The anecdote I’d follow up with that very quickly is from the movie Dolores Claiborne, Kathy Bates, Jennifer Jason Leigh. Kathy Bates is accused of killing her husband, and we don’t know if she did it or not. Actually, I think what she did was she was defending herself. So he was abusing her, and she finally. So she’s in jail, and there’s a prosecutor in the town that’s had it out for her for years. And there’s a moment where Jennifer Jason Leigh who is the daughter returned– she’s a lawyer– she goes into– and she’s talking to her mom and whatever– but then she goes to the prosecutor– and I forget the actor’s name– but I remember how she said what she said, and it was really important for me. She goes, “I’m asking you as an honorable man to drop these charges.” And he goes– he’s really angry, and he’s full of bluster, and his face is red, and he’s angry. And she goes, “I tried. So now, we’re just going to come in here, and we’re going to take this case apart.” And then she takes her mother out of the police station, but it was a moment where I just felt like, “I’m asking you as an honorable man to re-think your position here.” And there are moments where I’ve witnessed that, not verbatim in other people and other moments where I felt there were these moments of grace where people were saying, “I want to communicate across something here. Can you look past your anger and your frustration? Can you look past what you believe is happening versus what may have actually happened?” And so I love that moment. I love that moment. I have to go watch it again because I’m hoping I’m getting it correctly [laughter], but I just remember the way the camera lingered on her face and the beat between how she was saying it, almost exhausted, “I’m asking you as an honorable man,” and it just really broke me up. I was like, “Wow, I just want to communicate like that all the time with people [laughter].” But, of course, hey, capacity. But yeah. Yeah, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 25:20 | To take Steven’s anecdote and sort of spin into what I was not really arguing for, but sort of advocating for, the fact that you could A, have a real-world encounter like that, which encounters like that do happen. I have my own anecdote about it, but I won’t use that right now around my tailor who told me this story, but I realize that’s a super-bougie statement, “My tailor told me this story [laughter].” |

| S. FULLWOOD: 25:57 | Hey, on your own full humanity here [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 26:01 | Exactly. No judgment. You’re in a safe place. Safe place [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 26:07 | So not only that those encounters can happen, but that you would write a piece of entertainment in which one of its central emotional elements, it’s moment of impact– obviously, you described the extra beat in the camera angle, and the emotional force of that moment. That means that we have, as a culture, as a people, as a group, access and belief and faith in that story that you can appeal to people’s principles, and that it is possible, even if rare, that that appeal will be answered. But that’s a great thing. That is a wonderful, wonderful thing. And I would dedicate my life and my work to expanding the frequency and the fidelity of that appeal. That’s a good project, right? And I think that we’ve moved the dial on that in this country in the last 100 years. I think we’ve moved that dial. I feel like a greater variety of lifestyles and faces could have that encounter, and that the person that didn’t meet that call would feel an element of shame. And I think that that is a good thing. I think that’s a good thing. Not that there’s not lots of miles to go before we sleep and whatnot. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 27:49 | No, but as in past podcasts have taught me, it’s important to recognize progress. |

| C.T. WEBB: 27:58 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 27:59 | Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 27:59 | Mm-hmm. Well, what I wanted to say, too, to bring it back to, again, that question of white misanthropy is that I think what precisely happens is that principle– I’m writing down “principle” because I need to say something about that. What happens with white misanthropy is that it weaponizes precisely those aspects of us that run against the humanity we’re talking about, the humanity that is based on giving space or expanding the notion of the self to encompass others and acting on principle. White misanthropy precisely weaponizes the notion of revering thinking over feeling, of the self being this atomized, individualized, discreet object that doesn’t care about anybody outside of its purview. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 28:54 | Or itself. |

| S. RODNEY: 28:55 | Right. Or itself. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 28:56 | Because we’re talking about going against its own benefits. |

| S. RODNEY: 28:59 | Exactly. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 29:00 | And I have a story about that, too. But keep going, yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 29:02 | Right, but that’s what white misanthropy does, right? It weaponizes these things and kind of puts them together in this very neat, discreet package, which is essentially a fist, right? It’s a clenched fist. That’s what white misanthropy does. |

| C.T. WEBB: 29:24 | And it clothes– I mean, to add onto it– it clothes itself in the very principles that we are advocating for. I know we didn’t get a chance to get into it, but the LA Review of Books article you sent precisely talks about this, right, the continued historical failure of the human rights movement to address these gaping holes in the areas of the world and the nation-states and cultures that were advocating for human rights and where they utterly failed to apply the same rhetoric and principles to their own national interest. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 30:02 | Oh, absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 30:04 | And so, yeah, I mean, the hypocrisy of that– there’s probably a better word than hypocrisy, but that is a way– I mean, I agree, I do think that’s the way that white misanthropy works and is incredibly fleet-of-foot and adept at doing it, right? And it’s really good at deploying those tools. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 30:26 | And we haven’t talked much about Christianity, but I have to [inaudible] bring that in, as a sort of apocalyptic sensibility about, “I won’t get mine here, but I’ll get it over there,” kind of thing. So, therefore, where is the urgency to make this world, this place better? |

| S. RODNEY: 30:43 | Exactly, exactly. Because if your fucking happiness is always deferred [laughter], how expansive is your sense of self, of being a principled human being going to be? I mean, I’m glad you said this, Steven because I look at people like Jerry Falwell and the whole sort of white evangelical movement, and I think that’s it right there. That’s it. If I turn up on your doorstep– one of these white evangelicals– if I turned up on their doorstep, destitute, lost, hurt, hungry. They would go in the back and get their shotgun and chase me down the damn street. Now, that’s what they would do. And we know this from the anecdotal stories that we read, right? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 31:29 | Yeah, the [inaudible] ones, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 31:31 | So a nerdy qualification to that. So there’s two main theological thrusts within Christianity that deal with apocalypticism, one is called pre-millennialism and the other is post-millennialism. Post-millennialists– and it’s been a while since I’ve worked in this stuff– but one of these, I think, post-millennialism, basically, Christ will come after the Golden Age. These are the kind of Christians that would get on the Freedom Rider buses, and they believe that by improving the world, they were opening it for Christ’s return. The other type that you are criticizing and I feel rightly [laughter] is that Christ will come before the world is perfected. And so in its depraved state, Christ will come and then redeem it. And these are the versions of Christianity that you guys are talking about right now, which do seem to be ascendant in the culture, but have not always– that has not always been the case. |

| S. RODNEY: 32:32 | That’s a fair point to make, and I’m glad that you’re making it. You’re right. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 32:36 | I definitely like the distinction because the first group doesn’t have a lot of good press [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 32:41 | Right [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 32:42 | Yeah. That’s right [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 32:42 | No, no. That’ right. And they were absolutely integral to the civil rights movement. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 32:48 | Oh, absolutely. Almost every movement, actually. |

| S. RODNEY: 32:51 | Yeah, no. Fair enough. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 32:53 | Human rights movement. |

| S. RODNEY: 32:54 | Anti-war movement. Absolutely. And workers’ rights. Yes, yes, yes. All right. So I like where we’ve got to today. I mean, I have to say that, just as kind of a closing thought on my end, not that this has to be the closing thought for our conversation, but what struck me is that given that there has been this sort of failure across the board of capturing the promise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is that white misanthropy isn’t just white. There are all kinds of misanthropy around the world, right? It’s just the one that we, Travis, Steven, I, deal with daily, happens to have the “white” before it. But there’s all kinds of misanthropy, right? It’s just the major one that we have to kind of make our way through, hacking– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 33:57 | Navigate and think about it? |

| S. RODNEY: 33:58 | Yes, yes. Every day is white in this country. |

| C.T. WEBB: 34:02 | I’d like to actually give Steven the last word, but to add onto what you say actually, I do think that– and the jury is out very much I think as far as where the United States is going to end up in the historical record, but I do think that the real work of our generation and succeeding generations until the story of the United States is done is whether the nation can write a story about itself that is not predicated on the degradation of the black body, which is what its founding was all about, which is what the mythology of the United States was built on. And is it possible? It’s sort of like saying, “Can Christianity continue once you realize that Paul was an apostate?” Not Christ, right? Because the, “All men are created equal,” you still want to keep that as the gold standard, but the primary missionary of that message was an apostate and a liar. And so can the United States re-configure itself knowing that its primary evangelists were liars? And we’re not. I’m sorry. But, Steven, please? |

| S. FULLWOOD: 35:25 | No. Thank you for that, Travis because you brought me to an original point that I was thinking about earlier, and it was the idea about the big lie. Like, “What are we going to do about the big lie?” And we’ve been chipping at it– as Seph said– for a while. We’ve been chipping at it, chipping at it, chipping at it. And again, it’s not only white misanthropy. We’re also talking about other “misanthropies” as well. I agree with that. One final point I would like to make. It’s not even a point. It’s just a question, and it’s a question for our listeners and for anyone else who might either have come across this podcast or heard from someone who’s listened to it, and it’s like, “Do you need yourself in the pain of others for it to matter?” |

| S. RODNEY: 36:01 | Good question. |

| C.T. WEBB: 36:03 | Yeah, great question. So I think we’ll just close with Steven’s question. So gentleman thanks, as always, for the conversation. |

| S. RODNEY: 36:11 | Indeed. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 36:12 | Thank you. |

| C.T. WEBB: 36:12 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 36:13 | Bye-bye. [music] |

References

First referenced at 07:12

“James Baldwin (1924-1987) was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic, and one of America’s foremost writers. His essays, such as “Notes of a Native Son” (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-twentieth-century America.” Purchase through Amazon here.

First referenced at 23:22

“Misery loves company as Kathy Bates, Jennifer Jason Leigh and Christopher Plummer star in an atmospheric whodunit that’s part mystery, part human drama and wholly entertaining.” Purchase through Amazon here.

Episode 0101 – Comedy: Patrice O’Neal, Laughing Because It Hurts

Patrice O’Neal died in 2011, but his comedy is still hot. Stories that turn a bitter reality into laughter is this week’s subject. Should there be a limit on what comedians can say for a joke?

Michael Jackson: The One Percenters of Celebrity

TAA 0069 – Megastars like Michael Jackson seem to be exempted from critiques of their wealth. Rarely do you hear Jay-Z or Tom Hanks referred to derisively as “the one percent.” Why don’t we care about extremes of wealth in our entertainers?

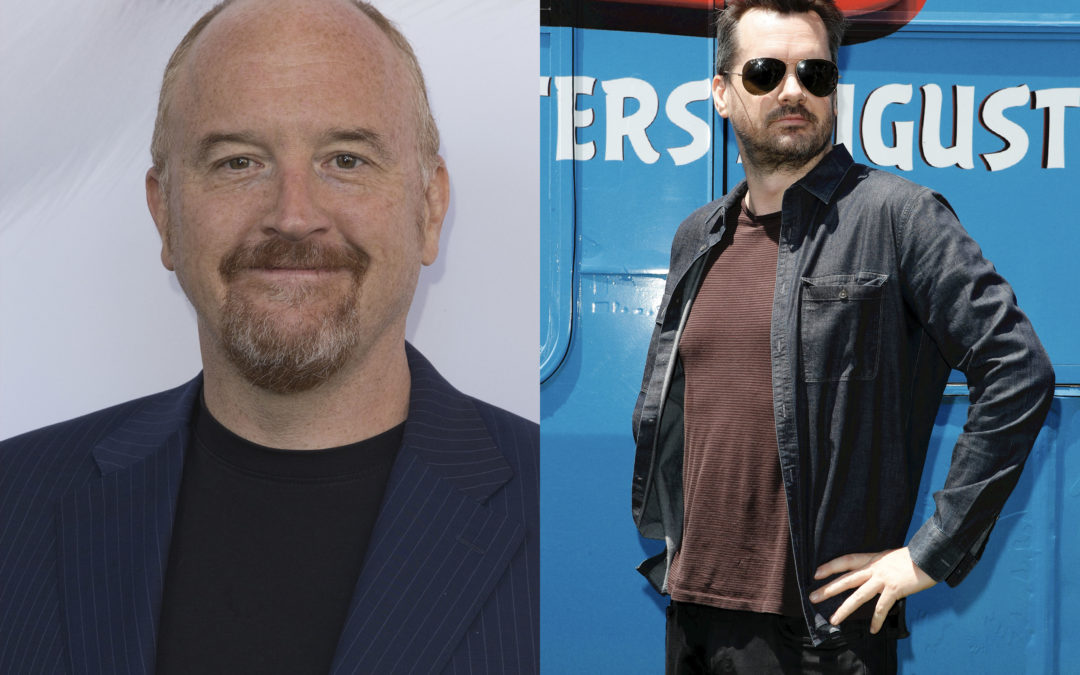

Episode 0098 – Comedy: Offensive Comedy and Its Virtues

There’s laughing at yourself, and then there’s laughing at others. While the former is virtuous the latter is indispensable to group cohesion. In this episode the hosts talk about Jim Jefferies and Louis C.K. What are the limits of comedy?

Pornography, Part V: Desire and Despair

TAA 0056 – The hosts continue their conversation about pornography. This week they explore the emotional cost of pornography. Who shapes our desires? And what happens when we are regularly reminded of what we don’t have?