0061 | March 4, 2019

White Supremacy: Institutional Misanthropy

What does institutional “white” power look like in the 21st century? In what ways are institutions oriented against people of color, and in what ways are institutions a result of that historical orientation? The hosts untangle the ways people use and are used by that history.

| C.T. WEBB: 00:19 | [music] Good afternoon, good morning, or good evening, and welcome to The American Age podcast. My name is C. Travis Webb, editor of The American Age, and I’m speaking to you from Southern California, and I am joined by my two very close friends. |

| S. RODNEY: 00:32 | Hey, hey, hey, hey y’all. |

| C.T. WEBB: 00:32 | Hi. The intro [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 00:35 | Hi, this is Seph Rodney. I am an editor at Hyperallergic, the most excellent art blog imaginable. I’m also a part-time faculty member at Parsons School of Design, and I’m speaking to you from the Boogie Down Bronx, where it is chilly but sunny, and I’m grateful to be alive. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 00:51 | And I am finally the third of this trio. I’m Steven G. Fullwood, and I’m one of the co-founders of the Nomadic Archivists Project. And I am coming to you from Harlem. And Harlem is cold, but it’s that cold spring cold where it’s a little bit warm if you stand over here, a little bit cold if you stand over there. But overall it’s just a dusting of snow out to remind you that it’s winter. |

| S. RODNEY: 01:15 | Yeah. Word. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 01:17 | Mm-hmm [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 01:18 | That intro reminded me a little bit of Phil Hartman’s intro from Groundhog Day when he was like, “There are hearts and hearts,” as that was very well said. I appreciate it, Steven. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 01:30 | I love that movie. |

| C.T. WEBB: 01:32 | So today, we’re continuing our conversation about white supremacy construed broadly, right, where we bring a lot of things into the topic. And this is to remind our listeners that we practice a form of what we call intellectual intimacy, which is giving each other the space and time to figure out things out loud and together. And today’s specific topic is on the institutionalization of what Steven has brought into the conversation and references [Ty Shah?]. Is that where you brought her [crosstalk], so. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:02 | Yes. Her name is [Ty Shah?], a wonderful black woman, a Panamanian woman in Atlanta, Georgia, yes. |

| C.T. WEBB: 02:09 | Okay. So in this institutional white misanthropy and in the sort of the ways that that institutionalization manifests– And before we started the conversation, I had volunteered to jump in because Steven reminded me of the topic yesterday, and immediately something came to mind. And I’d be interested to see what you guys think of it and then also just to where it goes. So the Jussie Smollett case. |

| S. RODNEY: 02:38 | Mm-hmm. |

| C.T. WEBB: 02:40 | I mean, I guess it will be a case [inaudible]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:42 | Well, it’s a case already, yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 02:44 | Yeah, yeah. It certainly– I mean, will be a trial and all the rest of it. And– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 02:47 | Goddamn. |

| C.T. WEBB: 02:49 | –and we can bracket, although we can talk about kind of the danger– or not the danger but the harm that it does to actual legitimate advocacy for hate crimes, etc. or against hate crimes, I should say. What I’d like to do is to contextualize that story for a second and say that using race, using white supremacy as a tool to manipulate cultural opinions has a very deep history, and it has traditionally worked out way worse for people of color. So, Emmett Till is, of course of the first. I mean, this is an analogous example of a white woman that accused a young black man or a boy– I mean, I shouldn’t call him a man. He was a boy. |

| S. RODNEY: 03:44 | Yeah. He was a boy. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 03:45 | He was a boy. |

| S. RODNEY: 03:46 | He was 13 or 14? |

| C.T. WEBB: 03:48 | Yeah, I just, yeah, some– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 03:49 | He was 14, I believe. Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 03:51 | I think 14 is right. And because of that accusation, he was murdered horrendously, awfully, terribly, horribly. And so, this woman used a narrative of white supremacy to have sort of a mob mentality unleashed on this boy. Of course, it was a turning point in the civil rights movement in the United States, but it’d been going on for a very, very, very– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 04:19 | Oh. |

| C.T. WEBB: 04:19 | –there just aren’t enough verys in there – long time. Long time, right? There’s a deep history here. So people using a narrative of white supremacy on either side of it, right? I mean, this is what individuals with cultural power do, is they use the accepted narratives to work their way, right, to make their will manifest in the world, whatever that happens to be. And now we are at a point in history where we have an example of it working on the flip side, let’s just be honest, in the most insignificant of ways comparatively speaking to its longer history, right? I mean, so this guy gets fired from Empire. Maybe there’s some consequences for him, some minor consequences and maybe some larger consequences for the culture at large, but nothing compared to the existential threat that was using this narrative for hundreds of years in the United States. So I just wanted to see what you guys thought of that example, what your feelings were about it in general, how the institutionalization of this manifests itself and has manifested itself at various points in time. Yeah. So please just jump in or take it in another direction if you like, but that was just the thing that occurred to me. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 05:47 | Seph Rodney, come on. Whatcha got? |

| S. RODNEY: 05:51 | Well, I was going to defer to you, Steven, because I think I’m still processing. It’s kind of a surprise question, but then it really shouldn’t be. I have to say that when I first read about the controversy – and I don’t hold it over the matter of a few days, almost weeks – my initial response was, “Oh yeah. That’s not surprising that this happened to this person.” It’s not surprising. It was a little weird, I thought. The noose thing seemed a bit, I don’t know– |

| C.T. WEBB: 06:22 | –a little on the nose. |

| S. RODNEY: 06:23 | Yeah. A little, no. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 06:23 | Yeah. A little off. Yeah. It was pretty [inaudible]– |

| S. RODNEY: 06:26 | Yeah. It was pretty– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 06:28 | –[inaudible] description, yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 06:29 | Yeah, but it’s also over determined, right? It’s like– it’s not enough to call someone– I mean, I’m reminded of that silly skit that– |

| What’s his name? From Atlanta? Has the name of the older actor, Danny. | |

| C.T. WEBB: 06:43 | Oh. [inaudible] Glover. Donald Glover. |

| S. RODNEY: 06:46 | Yes. Yeah. Donald Glover, thank you. I don’t know if you have seen this skit. I have to say– and this is at least partly due to me having been raised in the United States, essentially that I find it hilariously funny. It’s a skit where they’re doing a spelling bee, and Donald Glover is one of the people giving the words to the students to spell. And he, without breaking character, in all seriousness says, “Nigger faggot [laughter]. Nigger faggot.” And then, of course, then the white kids will say to it, “Can you tell me a sentence? I don’t know–” He’s like, “Look at that nigger faggot over there [laughter].” So I mean he was kind of like that. He was like, “You had the news,” and it’s not just nigger, not just faggot. It’s Nigger Faggot, right? That’s why I say he’s really overdetermined how much you hate this man because of his sort of obvious surveillances of his social being. Okay. So when it unfolded that he likely made it up, and I think his lawyers are still insisting that he hasn’t– |

| C.T. WEBB: 08:07 | Yes they are. He’s maintaining that he is innocent. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 08:09 | Yeah. Come on [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY: 08:10 | — but the preponderance of evidence points to him having done exactly that. I felt and I suppose now feel– I feel precarious. I feel like every single instance in which that narrative is used to lever up our outrage, our anguish about another black person being victimized, that it’s another moment when it begins to feel like that’s all we can bring to the table. All we can bring to the table is anger and anguish and outrage, which is this sort of the version of the pitchforks and torches coming out for people, right, where except we tend to do it verbally on social media platforms. At least, let me own that, one of my main outlets – I’m a writer – tends to be the social media platforms and the things I write for Hyperallergic and other publications. |

| S. RODNEY: 09:18 | That said, I was also helpfully reminded by Charles Blow that the counternarrative which is that, “Oh look, another black person is using playing the race card with respect to this white supremacy narrative in a false way, right?” He said, “That’s a racist argument. If you expect you to be responsible for what another black person has done or that you see that as a reflection on the “race,” that’s silly. That’s the definition of racism. Jussie Smollett has nothing to do with me. Nothing, right? So there’s a way in which the white supremacist’s narrative, the thing that can undo it is precisely the notion that a black person cannot stand in for black people, right? The synecdoche does not work. It is false. There is no one black person that stands in for the group. And to assume that that happens is silly. The problem though is that that’s kind of what goes into our understanding of what constitutes white supremacy – so this is a problem, right? – because we recognize that every time an institution oppresses, exploits a black person, we feel it has been done to black people, so. |

| C.T. WEBB: 10:48 | And that white people are the ones doing it. |

| S. RODNEY: 10:50 | Right. So that’s a problem. And I just talked myself into this corner, and I’m not sure how to get out. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 10:58 | That’s okay. We’ll help you out here. |

| S. RODNEY: 11:00 | Okay. Great [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 11:02 | I’m just going to offer some space, I guess. And so, where I thought you were going with stuff initially was what people have been saying all along now that Jussie Smollett has lied. That means every time somebody brings a case up and says, “Yes. I’ve been abused and I was attacked, blah, blah, blah,” that means it’s going to cast suspicion on that person, right? Are you lying? I’m like, “The bar is so fucking low for people who have been attacked and are trying to explain their cases to the police or whomever else.” And not to mention, “What were you doing out there? What were you wearing? Are you trans? What are you supposed–” Immediately suspicion is brought upon them. But all the trans men and women who have been killed just this year won’t get a tenth of the press that surrounds someone like Jussie Smollett. To go back to what Travis said though, I wanted to say something about this idea, where the tropes of white misanthropy is a really interesting one because so many people believed it was confirmation bias. However, in my circles with other people, I remember, I was like, “Oh that happened to him? That’s really sad,” but then I read the story, and I said, “Overdetermined.” It was like, “Hey, Empire nigger. Blah, blah, blah,” and he saw one, and then another one beat him up, and he had on a mask but he can see pink through that. No, no, no, no, no, no, no. It just sounded way too labored, way too– |

| S. RODNEY: 12:34 | So you were suspicious from the beginning. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 12:35 | From the beginning. |

| S. RODNEY: 12:37 | I mean from– Yeah. That could have been interesting. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 12:37 | I don’t think that– It’s not a black and white issue. It’s very nuanced in terms of how people responded to it at least on social media. There may have been that barrage of people who were like, “Justice for Jussie. Jussie for justice, whatever.” I was like, “This doesn’t sound right. This doesn’t pass the smell test.” A friend of mine who shall remain nameless is a reporter, and he wrote on Facebook what he felt about it. He says, “These things simply don’t add up. I’ve read a lot about it. I’ve listened to Smollett, all that, and they just don’t seem to add up. And people went after him. Some people came after him, and I thought it was interesting because they said, “First, you believe somebody, you give them compassion, and if you have doubts, then you keep them. You don’t broadcast them.” |

| S. RODNEY: 13:23 | Right. You keep them in reserve. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 13:24 | You keep them reserved. And I actually have a friend who signed a “Find out what happened to Jussie Smollett” kind of online petition, but refused to post it on his Facebook page because he was like he had doubts. So I think your thinking person – black, white, green, blue, whatever – was kind of like, “I’m not sure about this.” So I thought it was a really good example of– and I do believe he made everything up. I don’t buy the “Chicago police are on our side” by any manner, shape, or form. And so, it’s such a nuanced case of using white misanthropy to bring attention in a very charged environment. It’s always a charged environment no matter who’s in office, but Trump elevates this, and the hate groups and the Republicans have refused to hold him accountable. It’s that moment where people want to believe this is right and that’s wrong. Jussie for me, I remember asking someone. I was like, “Is he that popular? Do you people know him?” There were really dedicated white misanthropes walking around Chicago at 2 am in the morning with bleach and nooses. I just did not buy it [laughter]. I’m just like, “I just can’t seem–” I was like, “Hats off to you guys. MAGA hats off to you guys if it happened.” But no, I just didn’t buy it. |

| C.T. WEBB: 14:39 | So when I hear both of you, I feel like both of those things are true. I feel like Seph’s corner that he sort of uncomfortably led himself with his line of argumentation or just sort of thinking out loud about it, I think that’s right. And I think what you said, Steven, basically supports that, right? So I mean, what you’re really saying is that these racialized stories about intent and victimhood and persecution or whatever on both sides of it, right – so the ones persecuting and the ones being persecuted – are largely inadequate to the reality of 21st century America. And the thing that I– another sort of topical thing where I would say, “We’re just so flat-footed about how we talk about the institutional problems,” in part because the real problems are really hard and really difficult to deal with, right? How do we actually– so I just came back from a conference in Memphis, right, where it’s a 50% poverty rate amongst black Americans in Memphis. So it’s worse than Detroit. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 15:53 | And let’s talk about that for a second because what we’re doing here is– the reason why these stories have currency. The reason why Jussie Smollett’s story for me had so much currency, not truth, but currency along with other people was that because we’re talking about a culture that has suppressed and continues to suppress its discriminatory practices and outright violence towards people of African descent. That’s what we’re talking about here. So the reason why Jussie stands in for some people is because justice was never done for those gillions of mother fuckers that have experienced this and continue to. |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:25 | Okay. So– |

| S. RODNEY: 16:27 | No. That’s right. |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:27 | –let me jump in. I’m with you all the way– |

| S. RODNEY: 16:33 | Up to? |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:34 | –up to the phrasing of it being done currently. I just want to nuance it. I don’t want to say that it– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 16:42 | Oh, nuance it. Sure. |

| C.T. WEBB: 16:43 | –which is that what’s happening– I mean, Memphis is like the slaveholdingest of the slaveholding cities. It was a whole made-up slave market like Egyptian name. It is like the absolute– I mean, nearly sort of like the quintessence of white supremacy and its history. And it’s that history that gives us the world that we have today and that our completely inadequate historical consciousness in America prepares us to confront and deal with. It is probably the case today that the institutions as they are worked and navigated and moved through are not as structurally resistant to non– so people that are not would be “white.” It’s so clunky the way I’m talking about it. But to say that what we look at today in Memphis, what we look at today in Chicago, we look at today in Detroit, in the other parts of the country is the legacy of a system that has never been properly addressed ever– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 17:55 | Of course. |

| C.T. WEBB: 17:55 | –at any point. And that that, in fact, it’s not white supremacy, it’s not MAGA hats and nooses, and it’s none of that that’s the real issue. The real issue is that we are not committed structurally or institutionally in this country to redressing the poverty that we inflicted on the Africans of the African diaspora. And that requires a massive investment in infrastructure, a massive investment in NGOs in these areas. I mean, there are things that can be done. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:35 | Oh, no. Of course. Of course. |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:36 | There are literally policies that could be enacted. |

| S. RODNEY: 18:39 | Dude, the poor people’s campaign. There are a bunch of different things that people have tried to initiate. |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:44 | Yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 18:44 | Precisely. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 18:45 | Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:45 | And that are really, really, really hard. They’re really hard. |

| S. RODNEY: 18:51 | How difficult? |

| C.T. WEBB: 18:52 | You’ve got fully entrenched interests that aren’t about white supremacy, that are just about run-of-the-mill human narcissism. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:01 | Ah, okay. Okay. |

| C.T. WEBB: 19:03 | And I’m not saying that white supremacy or white misanthropy is gone. That’s not what I’m saying. I’m saying its effect on the system is smaller than the other cumulative, structural effects that are keeping people of color impoverished in this country. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 19:24 | And to our next podcast episode, how it keeps whites really disenfranchised. What white misanthropy actually does to whites. So stay tuned for that, listeners. We’re going to be talking about that. |

| S. RODNEY: 19:36 | Right. So let me address this because I want to make sure I understand you, Travis, because that’s a brick-heavy argument. What you’re saying is that– and I’m going to use– I’m going to try to use concrete historical examples. You’re saying that there’s a kind of inability or resistance to addressing the systematic– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 20:00 | Disenfranchisement? |

| S. RODNEY: 20:01 | Yes. Disenfranchisement of people of the African diaspora in the US because there’s more energy and more attention paid to essentially making money. So things like the Enron scandal, things like the Iran Contra affair, those are moments where what’s been mobilized is a lot of human capital in order to make money, right, and in order to push forward a certain political agenda. I’m thinking the Iran Contra affair. So those kinds of things you’re saying, actually, cumulatively, those kinds of concerns, political agendas, and essentially – and Trump is a spectacular example of this – they sort of institutionalize greed, right? The willing exploitation of people in order to make money off them. Amway is also a perfect example of this, right, which is where Betsy DeVos made her fortune. So those things, right, that kind of attention, that kind of concern, you’re saying altogether tends to weigh more or garner more attention and human capital than actively suppressing people of the African diaspora because you’re saying that on the list of things to kind of get done for a lot of people, suppressing African people is low on the list, right? You’re saying maybe third or fourth or fifth. They’re like– |

| C.T. WEBB: 21:46 | That’s right. It’s an ingredient. It’s just not the main ingredient. |

| S. RODNEY: 21:50 | Right. So– |

| C.T. WEBB: 21:51 | It’s saffron or whatever, in the history of– |

| S. RODNEY: 21:54 | Right. And the kind of mobilization of collective, institutional, and structural powers to address that historical disenfranchisement, I’m thinking would have to be at the level of a kind of like FEMA intervention right, where you literally pour millions of dollars into policies and programs that you know work, right, like microlending or– |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:25 | Yeah. Microlending is a good example. |

| S. RODNEY: 22:26 | Right? Or more equitable allocation of assets for school districts, right, because we know now that white districts tend to get millions more dollars than– |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:38 | That’s right, because of property values. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 22:39 | Oh, yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 22:39 | Right. Right. |

| C.T. WEBB: 22:41 | And then, to be super specific and then kick it to Steven. Memphis, for example, at this conference, a Memphian or whatever – I guess that’s what they call themselves – was talking– and I don’t recall the percentage. I believe he knew when he was detailing the situation, but it was, again, one of the top in the United States surpassing New York. Most homes in Memphis are not owned by people that live in Memphis. They are investment properties that are owned by people spread out across the world. And so you have this kind of fungibility of capital. That’s a structural issue that you could actually– that has nothing really to do with Africans or people of African descent, right? It really doesn’t have to– no, no, wait, wait, wait, wait. Wait, Steve. Let me just– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 23:27 | I’m just looking at you [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB: 23:28 | Today, in 2019, that choice is not being made because they want to disenfranchise the blacks in Memphis, right, because it’s a large part of the community. It’s the effect, right? It’s the effect of a historical reality which was that at one point in time, but now it means that you have to tell like ma and pa Australian, 60-something Australian, that their mutual fund investment in Memphis for their rental property which helps pay for their agroponic garden that they can’t do that anymore. That’s a much harder, more intractable problem. I’m not saying we shouldn’t address that problem. I’m saying we should get off the stick and start trying to address those problems. And things like Smollett and all the raging inside– and this is my period at the end. And all the raging on social media and in the media, in the more elevated media, only detracts from the real problem, which is this structural impediment to redistributing a historical wealth that was built on the backs of murdered and enslaved peoples of African descent. |

| S. RODNEY: 24:46 | God damn. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 24:47 | A wonderful period. I’m going to come back to a few things you said, but I really appreciate your kicking it off to me as you talked about the property investments in Memphis, because the example that I have for institutional white misanthropy deals with a case of reparations, and this is an article by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and he actually– |

| S. RODNEY: 25:09 | I know this. Yes. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 25:11 | –interestingly, the Smollet, Chicago– yeah. I’m sure you guys have read it before. I think we’ve referred to it. |

| S. RODNEY: 25:13 | I have indeed. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 25:14 | We’re talking about people who through their lifetimes have been disenfranchised by institutional racism, whether it’s Clyde Ross– The story basically follows Clyde Ross who was born in 1923 in Mississippi. He was young enough to remember that. His father had been told that he owned $3,000 in back taxes. So everything was seized. The farm, all the animals, and so forth, and they were reduced to being sharecroppers. You jump ahead to 19– I believe 1961, and Clyde Ross and his wife bought a house in North Lawndale, which was Chicago’s West Side and had largely been a Jewish neighborhood. So he bought a house and did not know that he did not own the house, and the equity he was putting in to the house, the money he was putting in, he was not going to benefit from it because he was illiterate. He didn’t know what he was signing and tried throughout his life to get it fixed, but he couldn’t. And so the sort of lending predatory practices that people did even when you were trying to do this interracial neighborhood thing, these kinds of examples pop up as institutional redlining based on loaning people money. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 26:31 | And even, there’s a quote from that I thought was really interesting from a book called Black Wealth / White Wealth by Melvin Oliver and Thomas M. Shapiro, where they say locked out of the greatest mass opportunity for wealth accumulation in American history, African Americans who desired and were able to afford home ownership found themselves consigned to central city communities where their investments were affected by the self-fulfilling prophecies of the FHA appraisers, cut off from sources of new investment, their homes and communities deteriorated and lost value in comparison to those homes and communities that FHA appraisers deemed desirable. And so going back to your point about the money part of it, and the ego part of it, and the selfishness part of it, absolutely. Absolutely. Race– So when Toni Morrison said that the race is the least reliable piece of information you have about somebody, she was referring to her, I think, sixth novel Paradise. It might have been her sixth, sixth or seventh. Seventh. Seventh, as a matter of fact. And so, what I think I agree with is that it can be a distraction rather than to really address the systemic really deep painful things that look into our human soul and say, “Do we really believe that we are better than other people?” That’s just too hard. That’s just too hard because it means, I think, it might upend everybody’s sort of mental– the brain would explode. There’s just not enough RAM to understand how we feed into a system– |

| C.T. WEBB: 28:05 | Great analogy. |

| S. RODNEY: 28:06 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 28:07 | –that undermines our humanity in really sinister ways, in terrible ways, and has for years, and continues to. So in that way, I totally agree with you. |

| C.T. WEBB: 28:15 | All right. Can I add something to what you said it before I leave it. Maybe we can give Seph the last word since we’re coming up on 30, which is that I, in complete agreement with an addendum that I actually believe that if you were to press someone like Steven Pinker or kind of these– maybe Sam Harris even, these people that are sort of the forward guard of kind of the narrative of optimism, which, to be fair, I think is a conversation to have. I’m not a pessimist, and I think that there’s good conversations to be had around progress, but I really do feel like if you were to press them into a corner and you could get a true response out of them, that they would say on balance, things worked out better for African Americans, Africans that were forced into slavery that helped build America. That is the argument that you are left with when you want to be a booster for progress in the way that they are– in the way that they are boosters for it. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 29:29 | Oh, no. The way they understand progress. Is that what you mean? |

| C.T. WEBB: 29:30 | Yeah. To say that black peoples are better off having been forced to come to America, ultimately. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 29:38 | Oh that [inaudible] argument. Oh, yeah. |

| S. RODNEY: 29:40 | Damn. |

| C.T. WEBB: 29:41 | Yeah. So it’s a stupid argument, but it’s a feeling, right? It’s a feeling, and I really do think that amongst most people, that is actually a core belief that they would say, “Oh, it’s horrible. It’s terrible. All these things are awful, but–“ |

| S. FULLWOOD: 30:00 | Yeah. But their lenses are pretty dirty, and also they’ve been fed and educated in a way that doesn’t even allow them to imagine what other kinds of life existed outside of [inaudible]. |

| S. RODNEY: 30:10 | Sure. That’s precisely right. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 30:11 | Yeah. That’s pretty good. |

| S. RODNEY: 30:11 | That’s precisely right. So that’s a bankrupt position to take. So let me try to tie some things together. What I think in the last exchange you had, Travis and Steven, and I think what fell out of that last exchange for me was that Steven was saying, “Yes, this is true. At the same time, while a lot of energy and capital has been used essentially in the service of making money off of–” and whether or not that money gets made through exploiting other people is sort of neither here nor there for the people who are making money. Typically, it does exploit other people, and typically, it does oppress other people, but the aim is, again, political agenda is making money or making money first and political agenda is perhaps secondary. And making money includes individual money and also keeping family wealth. What Steven has added to that is to essentially say post World War Two in the US, black people were systematically cut out of the one end– and this is the argument that Coates made, right, that black people were systematically cut out of the one shining exemplary way of making and holding wealth in the family, that is property, right, owning property that would essentially increase in value over the years. |

| S. RODNEY: 31:43 | So what I hear is, on the one hand, yes, there’s a long history in which though the energy that has been mobilized structurally and institutionally, largely in the US, has been specifically geared towards, to say it in the crudest way, keeping black people down, right, to keeping them poor, keeping them disenfranchised, keeping them disempowered, but we’re also concluding that at some point, this sort of second stage rocket leaves the satellite, and we start thinking less and less about black people and keeping them down, and we think more and more in terms of these abstracted ways of making money, i.e., Enron, right? How much can it– or the savings and loans crisis. How much can it hurt if we just allow people to take out as much money as they want, and equity in their housing. They can just pay it back. And then, we’ll make these very complicated tranches of these collateralized debt obligations and blah, blah, blah, so it gets abstracted, abstracted, abstracted until we actually start to lose sight of these people of African descent and what has historically been done to make sure that they are kept poor, right? |

| S. RODNEY: 33:07 | So what I’m saying essentially is that, from the conversation I am taking that this is precisely part of the dilemma around white misanthropy, right, in that historically, it is rooted in disenfranchising those black people over there. In the 1960s, you could have a white family point, right, like they pointed at Emmett Till and say, “That one there, he did that. He’s bad. Go get him.” But since then, we’ve become less and less able on both sides, right? Less and less able to point to particular people because the means of wealth accumulation, right, becomes so abstracted that it’s not like you can say, “Those white people over there,” or, “Those black people over there are the ones that offended me.” So part of our problem is that we haven’t figured out the language by which to talk about that institutionalized, that systematized way of making money off the backs of other people, exploiting other people, right? We want to include it into a racialized discourse, but it actually slightly sits outside it, right? It began there, but it’s not there anymore. So that’s partly our dilemma. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 34:31 | I think that part of that dilemma, Seph and Travis, is because people who are the poorest of the poorest of the poorest of the poorest, intergenerational poverty, undereducated, and so forth still believe that one day, they could be a millionaire, or one day they could be rich. And I think that that they’re clouds. That’s just an ingredient of, I think, what stops people from actually seeing or wanting to believe or wanting to really do the intellectual work or the hard work around that particular thing that people want to be rich because that’s the best dream that they have. |

| C.T. WEBB: 35:03 | Right. |

| S. RODNEY: 35:03 | Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 35:04 | Yeah. Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 35:04 | And there are just more poor people, a lot of people, but I think that that’s the largest group. Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB: 35:09 | Yeah. I think that’s absolutely right, and I think that’s a fantastic summary of the discussion, Seph. It would say, it’s one of the reasons that I’m not that bullish on Bernie Sanders. Everyone talks about how radical Bernie Sanders is. I am actually entirely in favor of reparations. I don’t think you can necessarily– I don’t think you can just hand out a check to– I mean, that’s not going to do it– |

| S. RODNEY: 35:31 | Yeah. That’s not going to do it. No. |

| C.T. WEBB: 35:33 | –but there are some very well thought out smart plans about how to go about– |

| S. FULLWOOD: 35:37 | Of course. |

| C.T. WEBB: 35:38 | I am entirely– |

| S. RODNEY: 35:38 | Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB: 35:40 | If you want to, you can’t– as far as the economics go in the United States, I’m not talking about globally, but in the United States, you cannot disentangle race from economics. Not yet. Maybe in 200 years, maybe in 300 years if we did the right things, but you can’t do it today, and that’s why the Bernie Sanders thing– In the United States, if you want to redress income inequality, which is a serious problem and it needs to be addressed, race has to be part of that discussion, and reparations have to be a part of that discussion, otherwise you’re not serious about it in the United States. And so that’s why I’m just not that bullish on him. So I’m sorry. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 36:18 | I’d say Bernie Sanders and others basically feel like you’re just giving people, what you said, a check. And it’s like, “No, it’s much more in-depth than that.” We’re talking about better schools. We’re talking about better neighborhoods. We’re talking about a clear path to success in this culture where capitalism is regulated. This is what I’m talking about. |

| S. RODNEY: 36:36 | Absolutely. And I think, that’s a good place to stop. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 36:40 | Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB: 36:41 | We’re well over. Thank you, Seph. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 36:45 | Thank you, Seph, Travis. |

| S. RODNEY: 36:46 | No. Thank you all for that discussion. That was really illuminating. |

| S. FULLWOOD: 36:48 | That was fun. |

| S. RODNEY: 36:48 | I really appreciate that. Thank you. |

| C.T. WEBB: 36:49 | Yeah. It was wonderful. Until next week. |

| S. RODNEY: 36:52 | Definitely. [music] |

References

First referenced at 26:31

Melvin Oliver and Thomas M. Shapiro

“Thomas M. Shapiro is a professor at the Heller School for Social Policy, Brandeis University and is the author The Hidden Costs of Being African American and the co-author of Black Wealth/White Wealth.” Amazon

“Melvin L. Oliver is the sixth president of Pitzer College, an award-winning professor, author and a noted expert on racial and urban inequality.” Pitzer College

Episode 0101 – Comedy: Patrice O’Neal, Laughing Because It Hurts

Patrice O’Neal died in 2011, but his comedy is still hot. Stories that turn a bitter reality into laughter is this week’s subject. Should there be a limit on what comedians can say for a joke?

Comedy: Maria Bamford, How to Maintain Mental Health

The cliché goes that “laughter is the best medicine,” but the idea’s been around for thousands of years, so it’s probably best to call it “wisdom.” How can comedy help us cope with trauma?

Episode 0098 – Comedy: Offensive Comedy and Its Virtues

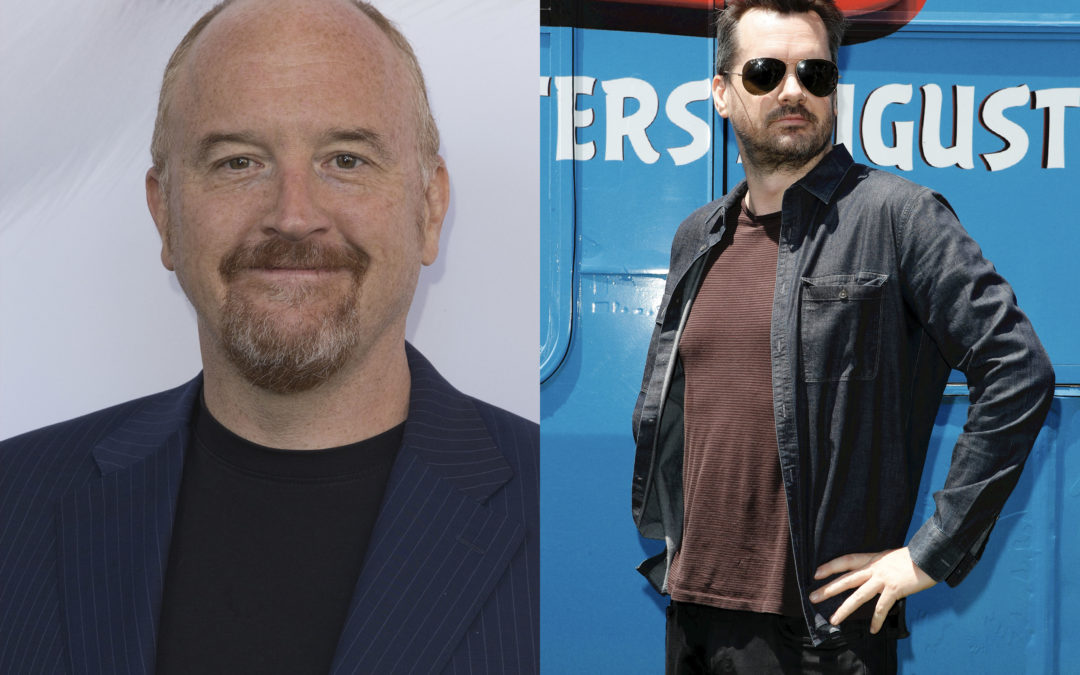

There’s laughing at yourself, and then there’s laughing at others. While the former is virtuous the latter is indispensable to group cohesion. In this episode the hosts talk about Jim Jefferies and Louis C.K. What are the limits of comedy?

Humor: What’s so funny?

The hosts take a personal look at what they find funny and why. Fair warning, political sensitivities aren’t off-limits.