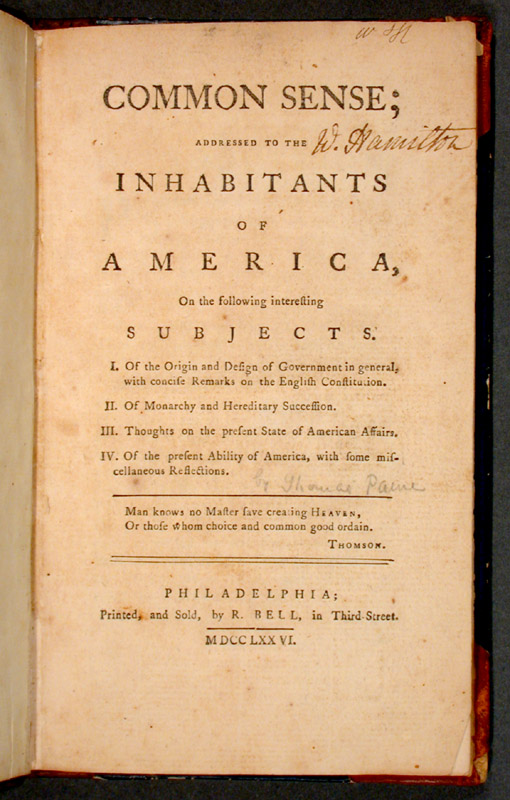

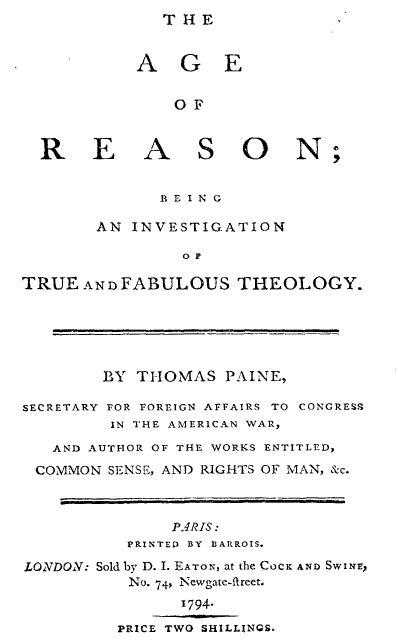

When we visited, we skipped the much-discussed amusement park rides on the third floor – my understanding is that one of them involves a virtual flight over D.C.’s monuments in search of biblical references. On the second floor, however, the motivation for this heavenly flight becomes clear: the Bible, according to the museum curators, inspired the American idea. This Christian nationalist story is not at all surprising, given the predilections of the museum’s sponsors. In their history, what has made America America is the Founders’ reliance on biblical ideas and, well, the Providential Unfolding of God’s Word. This has obvious implications for the kind of future Americans should aspire to, aligning with the more or less virulent strains of contemporary conservative social politics. On the second floor it becomes awfully clear why they’d care to build a museum like this in the first place. Lots of commentators have pointed out the problems with this story of American history (see here and here and here). In honor of Paine Day — Thomas Paine’s birthday, January 29th, marked as a holiday by freethinkers and infidels in the 19th century—I want to draw attention to the Museum’s brief but telling treatment of Paine by way of suggesting a better history.

0 Comments