0040 | October 8, 2018

Potlatch Sneakers:The Economics of Social Status

C. Travis Webb, Seph Rodney, and Steven Fullwood discuss why human beings of limited economic means purchase luxury items–such as expensive sneakers. Who gets to ask the question, how does it manifest across culture, what do these items mean?

| C.T. WEBB 00:19 | [music] Good afternoon, good morning, or good evening, and welcome to The American Age Podcast. I am C Travis Webb, a PhD in comparative literature and editor of the American Age. And today I’m speaking with Seph Rodney and Steven Fullwood. Gentlemen, you guys want to introduce yourselves? |

| S. RODNEY 00:32 | Sure. I’m Seph Rodney. I am an editor at Hyperallergic, the online arts blog. And I teach a research methodologies course at the New School, and I’m speaking to you from the South Bronx, New York City today. |

| S. FULLWOOD 00:49 | Good morning, good afternoon, good evening. I’m Steven G. Fullwood. I’m a co-founder of the Nomadic Archivist Project and consulting company that specializes in working with individuals and organizations to shore up their archives, specifically, people of African descent. And I am coming to you from planet Harlem [laughter]. |

| C.T. WEBB 01:10 | It’s funny because Seph had just suggested that we should identify where we’re from as a mark of professionalism. And I probably neglected to do that. And I wonder if it’s because I’m not really particularly thrilled where I’m speaking to you from. So I live in Orange, California, which is epicenter of conservative Southern California. So that’s where I hang my hat. |

| S. FULLWOOD 01:30 | Is that the OC? The OC, right? |

| C.T. WEBB 01:32 | That is the OC, Steven. Thank you for that [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY 01:37 | And we should also likely remind our listeners that our show is all about intellectual intimacy, so welcome to this. |

| S. FULLWOOD 01:43 | Yes. |

| C.T. WEBB 01:45 | So today we’re going to practice intellectual intimacy around a topic that Seph suggested last week. So Seph, I’ll just let you intro us, and I know Steven has some stuff to say about it as well, so. |

| S. RODNEY 01:54 | Precisely. I did email both of you yesterday after I jotted down a few thoughts while I was at work. Basically, this issue has stuck in my core for a long time. I immigrated from Jamaica when I was around six or seven years old. And I grew up in a city in which I felt constantly held to this standard of essentially a sort of kind of coolness that was commensurate with what I wore or rather was read through what I wore. So I remember– and actually, I just thought of this. This might be like the traumatic memory that’s at the center of this whole dilemma for me. But I was probably seven or maybe eight, and my parents had just given me the money to go up the street and buy a new pair of sneakers. And I was so thrilled with these. I remember the name. They were called Jets, and Jets were written on the side, and they were gray and white. And they just looked like I could run faster in them. And so I bought these shoes, and I was showing off to my friends around the way, Ronnie and Ralphie, and there may have been somebody else. And I showed them my Jets, and they just started clowning me. They were like, “Oh, you bought Jets. Oh, that’s rich.” And I was so foolish for having spent money on something that wasn’t even in style at the time, and this hasn’t shifted a lot since the late ’70s. Puma and Adidas were the ascendant styles. Reebok came in a little bit later. |

| C.T. WEBB 03:41 | I remember Pumas actually. That was a big deal. |

| S. RODNEY 03:43 | Sure. Yeah. The suede ones with the fat laces that guys used to rock. So the deal is since then, I have made it a point of never spending money on athletic gear. I had my mom buy me expensive basketball sneakers when I was in high school, and I always felt guilty about this shit because I knew that I would wear them for a few months and that’d be 60, 70 dollars just gone. I did break this rule a few years ago when I bought a pair of high-top Adidas for myself when I finally had like a little money squirreled away. And I wore them for maybe five times. And then I realized that the footbed actually didn’t fit me very well, so I just gave them away. |

| S. RODNEY 04:35 | Anyway, all of this backstory is to say it bothers me when I see people around me in my neighborhood, the South Bronx, which is rather economically depressed. It is not necessarily poor, it’s working class. It is a very active neighborhood. It is not on the verge of falling off the map at all. But I see people around me as I did when I was a kid in the North Bronx constantly rocking these really expensive sneakers. And I see them around. I know they’re expensive because I see them advertised in magazines and websites. Air Jordans, of course, are the ones with the most staying power. I mean, there’s got to be, I don’t know, hundreds of varieties of them. And I see them around constantly. And I keep saying to myself, “Why would you spend $250 on a pair of sneakers when you might save that money for X, Y, or Z?” |

| S. RODNEY 05:35 | And here’s where I feel really uncomfortable doing this. I make the assumption that they’re being fiscally irresponsible or they don’t have the means to afford to buy several pairs of those shoes. And I’m making these assumptions based on certain cues, right? Certain kind of socioeconomic cues like how well they’re dressed, whether they’re pushing a baby carriage, what kind of baby carriage, where they’re shopping, the fact that they’re taking public transportation, all of those things. So I want to say it bothers me because there’s a sense that underneath all of it, that they are buying into a claim that their social status has something to do with what they spend money on rather than what they earn or what they culturally produce, right? Because I don’t earn anything doing this podcast, but it is, for me, a significant cultural production. And I take some of my self-worth from doing this. |

| S. FULLWOOD 06:44 | Oh, okay. |

| S. RODNEY 06:47 | I do not measure my self-worth by the labels that I wear. And I feel like that’s the fundamental mistake that is being made. And it’s not only being made here in the South Bronx, but it is being propagated by American popular culture. |

| S. FULLWOOD 07:03 | Oh, yeah. Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 07:06 | So that’s my spiel. |

| C.T. WEBB 07:08 | All right. All right. Steven? |

| S. FULLWOOD 07:10 | Okay. So Seph, as I mentioned pre-broadcast, I was so excited by this question because it brought up a lot of things for me. And I started writing down notes shortly after we began talking. And I was thinking about I wanted you to kind of parse or both of you kind of work with me to parse the act of looking at someone who may or may not be able to afford something in a culture that as you mentioned is relentless marketing a view about your value in this culture, right? And I also wanted to sort of for us to think about the privilege you have of being able to do that from your position, your economic position, your sociological position and when you said you don’t judge yourself by labels, but we are dealing in labels. I know you’re talking about corporate labels. But I’m also talking about who gets to decide who can have what? So that’s kind of where I want to start. |

| S. RODNEY 08:12 | Okay. Good. Good. Good. Great. |

| S. FULLWOOD 08:16 | So that’s a little bit of a lot of stuff, but. Yeah. But I wanted to parse this. Yeah. |

| C.T. WEBB 08:20 | Yeah. So a couple of things I had thought about throwing into the mix is one is a sort of neurobiological, and then the other is kind of cross-cultural. One, the actual impulse to spend when your current circumstance or future circumstances are not hopeful or are in fact bleak, it’s probably built into us. So if your days are that dreary, you’re looking for anything that’ll pick you up. And so it becomes the calculation of saving the money for some future day when it might be worth more or purchase you something of more lasting value and the calculation of purchasing a pair of shoes today that are going to make you feel better immediately when you’re not even looking at graduating high school or you’re not looking at having anything other than a 40-plus hour a week job at Walmart or you’re looking at your position in the culture. I think it becomes completely understandable that people would choose short-term rewards over long-term gains, even if that’s problematic. |

| C.T. WEBB 09:46 | Secondly, I think it’s just the American version of what happens all over the world. And I would cite as a couple of examples, the completely disproportionate outlay and expenditure of religious ceremonies in India or in Central America as it relates to yearly income. So by some estimates, 40 to 60 percent of people’s annual income is spent on religious ceremonies. |

| S. FULLWOOD 10:20 | Gotcha. |

| C.T. WEBB 10:20 | And that’s about pageantry, that’s about performance, that’s about sort of an investment in a cultural signification that is not altogether unlike a pair of shoes. So those are just a couple of things that occurred to me even though I would like to also own up to the fact that, of course, I feel similar judgments to Seph as reflexively, right? I’m not saying like, “Oh, somehow I float above.” And absolutely not. I see things like that and like, “What the fuck is wrong with you? Like why are you doing that?” And I myself, when I was younger, have had issues with overspending impulsively and judge myself harshly for that. So anyway. They’re additional factors but not to suggest that somehow I feel disconnected from the problem. |

| S. RODNEY 11:19 | So I just want to [inaudible] second and talk about what I think is happening to my initial– I’m not even sure if it’s an argument. Maybe it’s a claim. What I love is that given what Steven has so far said and what Travis has so far said to me, I can feel like the very rough edges of the– let’s call it the sharp blade I held in my hand, right, which is that claim just immediately start to get sanded down, right? So that neurobiological argument makes perfect sense to me. The drawing an analogy between spending money on expensive shoes versus on religious ceremonies also makes perfect sense to me. Steven’s suggestion that I really think about the sort of politics of my own looking, of my own position and how I get to actually sort of– essentially, I think what Steven is suggesting – and this is something that I do want to delve into – is that there’s a kind of privileging of my own position as slightly outside of the culture, right? Like I’m saying I can stand outside this thing and I’m not really sort of– |

| C.T. WEBB 12:35 | The flaneur in the world but not of the world. |

| S. RODNEY 12:36 | Yeah. Yeah. I’m sort floating and looking and saying, “Oh, look at that and look at this,” and assuming that I’m not fully immersed in this thing myself [crosstalk]. |

| S. FULLWOOD 12:47 | Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 12:48 | Right. And I want to admit right now that there is a way in which this social performance of myself is really meaningful to me. I just don’t happen to subscribe to Air Jordans. I do think when I go to a particular kind of art event that it’s important for me to be dressed in the way that I think is comports with the way I see myself in this sort of socioeconomic picture. |

| S. FULLWOOD 13:21 | Absolutely. |

| S. RODNEY 13:23 | Right? So I am doing that too. And I totally recognize it. I think where I would begin to separate myself out is I would say – and this is the story I was thinking I would tell, and this seems like the appropriate place to tell it – and Travis kind of knows this already - when I left Southern California in 2006 to go to London to work on this PhD, I was earning around 52,000 a year, maybe 53, something like that working at Emporio Armani in Beverly Hills, and I was miserable for [crosstalk]. |

| C.T. WEBB 14:01 | Right. That is a fact. |

| S. RODNEY 14:03 | Yeah [laughter]. Travis was there through a lot of that misery, and he helped mitigate it, frankly. So I was poor, dirt poor from basically 2006 to maybe last year. Last year was the first time I actually made as much money as I had left on the table essentially when I left Southern California. This coming year, I do stand to make more. Hallelujah. But I was poor for almost 12 years. And when I say poor, I earned 16, $16,000 in 2012 according to my taxes. And I know that there were years I earned less than that. |

| C.T. WEBB 14:49 | For sure. |

| S. RODNEY 14:49 | So there were lots and lots of moments in my life as a 30 to 40-year-old man where I wasn’t earning shit and I felt bad about that. I didn’t have it. So I had to do this sort of [inaudible] sort of monk-like I’m going to self-denial thing. So when I see myself doing that, there’s a part of me that gets disgusted when I think that other people aren’t doing the same for themselves. And that’s not fair. I know it’s not fair. I– |

| S. FULLWOOD 15:28 | I’m just glad you said it. |

| S. RODNEY 15:29 | –definitely admit that. |

| S. FULLWOOD 15:29 | I’m so glad you said it. I can just pass over a few things I wanted to say, so that’s perfect. |

| C.T. WEBB 15:33 | But okay. So– |

| S. RODNEY 15:35 | Yeah. Please do. |

| C.T. WEBB 15:36 | Well, let’s try and get into it a little bit because I don’t know that that’s unfair. So I mean, of course, there’s a significant part of me that goes like, “Yeah. Of course, that’s not fair, blah, blah, blah, blah.” I come up with a host of reasons for it. But I’m talking about everyday world of how bodies interact and how we move through the world. Is that not a little bit fair? Is it not fair for Seph to hold up his own choices and own sacrifices as worthwhile and perhaps worthy of emulation over other– and I’m going to let you jump back in it because honestly, I’m playing a little bit of Devil’s advocate not in a sense that I’m trying on a hat I don’t think that has validity. I’m just, of course, I see some other aspects to the argument, but I don’t know that what Seph is describing isn’t a valid place from which to evaluate other people’s choices. |

| S. FULLWOOD 16:35 | I think it’s simply a place, a perspective. I don’t think it’s– and neither one of you suggested that it is the place to be. But it is a place. And so the frustration that you feel about seeing people who may be overspending or not saving or whatever it is. So I was curious about your frustration with the apparatus that allows for a lot of this to happen. And so that was one of my major questions. And I was thinking– well, it’s almost like anti-Black sentiment. It’s very easy to adopt. And so it’s very easy to say, “What are those poor people doing?” And I grew up around people like that. My dad’s that kind of guy, and I was like, “Dad.” He would say, “A man isn’t a man if he’s not working.” I’m like, “What if there are no jobs? What about intergenerational poverty? What about being undereducated, being miseducated? What about all these sort of factors that as well as the war on poor people, not the war on poverty–“ |

| S. RODNEY 17:35 | Right, right. |

| S. FULLWOOD 17:36 | –right, which is what I was coming up with because– so just a very brief in terms of being transparent, where I come from, I remember going to school. And I lived in a working class to poor family and that’s how I grew up. And I remember going to school. I think I was in the second or third grade, and I came to school with a shirt that was torn. But for some reason, I didn’t think about it. I was just kind of going along and enjoying my life. And my teacher tells me, “Well, I want you to go to the principal’s office,” right? And I sat there. I remember sitting there, and the principal came over and said– not the principal but a secretary said, “I want you to go over to that box and pick out any shirt you want.” And I was like, “Okay. Great.” So I picked out this yellow shirt that was checkered, and I was just so excited about this yellow shirt, about getting it. But it only occurred to me later on by the way I was being treated by my classmates that I was poor and that my mother oddly enough didn’t catch me in that shirt. I think it was a play shirt. But I was so interested in just wearing what I wanted to wear that that stood out as a moment of clarity for me about your value is with what you wear, and your value is with what other people say it is. And like you, Seph I was very anti-label and very anti all through high school and much of my life, I cast a wary eye on people who solely judge people by what it is that they look like, whether it’s what they wear or how they look. And I think that– |

| C.T. WEBB 19:14 | But wouldn’t we– yeah. No. I hear that, but wouldn’t we cast the same– I’m actually just seconding you here. Really, I’m not arguing against it. Wouldn’t we judge the same sort of reflexive knee-jerk response of someone that was judgmental about where other people went to school or– |

| S. FULLWOOD 19:33 | Well, no. |

| C.T. WEBB 19:33 | –what kind of books they read or what kind of restaurants they eat at or whatever? |

| S. FULLWOOD 19:38 | Intellectual, but parsing it– really we’re talking about whether or not you have the right to be here or whether or not you have a right to your own life choices. That’s what we’re getting at. So [crosstalk]. |

| C.T. WEBB 19:49 | Okay. But can I– |

| S. FULLWOOD 19:50 | Well, I just want to say one more thing. |

| C.T. WEBB 19:52 | No, no. Yeah, yeah. Please [crosstalk]. |

| S. FULLWOOD 19:53 | The [inaudible] my impatience with it is that we’re not looking at sometimes what the invisible parts of it. We’re blaming people for the choices that they’ve made because they don’t agree with our choices and the choices that we think we should be agreeing with. We’re not looking at the structure of the US. We’re not looking at tax breaks for rich and for the corporations. We’re not looking at those things with the same critique. |

| C.T. WEBB 20:17 | Well, mostly because we only have 30 minutes. |

| S. RODNEY 20:23 | Yeah. That’s right. |

| S. FULLWOOD 20:24 | I know. Really, trust me. There’s a lot of [crosstalk] [laughter]. |

| S. RODNEY 20:29 | No. No. No. But let me just jump in and say this really quickly. Actually, Steven, I am. |

| S. FULLWOOD 20:34 | Okay. |

| S. RODNEY 20:34 | When I’m doing those things that you just mentioned, critiquing the structure of essentially social value, I absolutely do that. |

| S. FULLWOOD 20:46 | Okay. |

| S. RODNEY 20:46 | I do it in my intellectual life, I do it in my daily life. I actually do critique when I have the opportunity, the financial arrangements or rather legal framework that allow people who are wealthy, already wealthy to allow corporations– |

| C.T. WEBB 21:07 | To get more wealthy. |

| S. RODNEY 21:07 | –to take fuller advantage of us. |

| S. FULLWOOD 21:10 | Oh, yes, yes. |

| S. RODNEY 21:12 | No. I absolutely hate that. So to a great extent, I’m a sort of equal opportunity– I don’t know what the nice way of saying it is |

| C.T. WEBB 21:22 | Critiquer? |

| S. RODNEY 21:22 | What? |

| C.T. WEBB 21:24 | Critiquer. |

| S. RODNEY 21:24 | Critic. |

| C.T. WEBB 21:25 | A critiquer. |

| S. RODNEY 21:26 | Critiquer. I like that. Critiquer. I’ll take that. I am, and I recognize again that that moment that I see that person – and thank you for reminding me of this, both of you – when that moment when I see that person pop up into my sight, right? And my sight is doing all this sort of parsing as I look at them, I do not see the invisible parts of their lives, or rather there’s lot of parts of their lives that are invisible to me. |

| C.T. WEBB 21:59 | Of course. |

| S. RODNEY 22:00 | And I’m making judgments on just what I can grok in that moment of sight. |

| S. FULLWOOD 22:05 | I see. |

| C.T. WEBB 22:08 | So can I say Steven, you have essentially made the argument for capitalism. When you say that people should be allowed to do what they want to do and be what they want to be and not have that regulated– and regulated is a heavy-handed word. It’s just what came to mind. I don’t mean that in that sort of laissez-faire way. But I just mean not have that circumscribed by people who know better. That is essentially a capitalist ethic, which you are essentially [inaudible]. And I actually think that the whole anti-capitalism sort of boogeyman knee-jerk reflex reaction– and we probably can’t do a podcast on this. It’s too long a conversation– but I actually think that it is born out of the long history of contemptus mundi in the west. Contemptus mundi meaning contempt for the material world. And I think I do not fear fundamental human appetites. And I think that the reason that the largest market online is pornography is because people like to fuck, and so I don’t have a problem with that. And I mean, one of the areas of where you could sort of earmark a great deal of freedom of expression is around the varieties of pornography that exist. And that is just like naked, stripped bare capitalism. People put these sites up, they film people fucking, they do all this stuff because they’re going to get eyeballs on it. |

| C.T. WEBB 23:55 | So I have less skepticism in my 40s now about the evil– I mean, I have more skepticism about the line of argument that immediately brands the evil of capitalism as the heart of our problem in the United States. I think the heart of our problem in the United States is a lack of principles and virtues and a certain lack of ethical center. But anyway, I don’t want to go too far off topic because I do want to stay with Seph’s shoes. And I think you had a valid response but it was just listening to what you were asking for Seph out of that moment to me felt like a pretty solid justification for some kind of economic liberty. So I’m sorry. Go ahead. |

| S. FULLWOOD 24:53 | I just want to say thank you very much for that. That’s all I want to say because I’m going to think about that. |

| S. RODNEY 24:58 | Okay. Okay. Like okay. |

| C.T. WEBB 25:03 | Can I excise economic and say material liberty? I mean it on a deeper level because these shoes mean more to the people than $250. That’s not what it means to them, right? |

| S. FULLWOOD 25:13 | Oh, no. Absolutely. |

| C.T. WEBB 25:14 | It’s not– |

| S. RODNEY 25:15 | Which is a good point to make. Thank you for that. Again, I feel like this claim that I came in the room with, which was bright and sharp is now like sanded down to like a butter knife. So let me– |

| C.T. WEBB 25:29 | You could still shiv some people with a butter knife |

| S. RODNEY 25:31 | Right, right. But let me say this. |

| S. FULLWOOD 25:33 | Wow, wow. |

| S. RODNEY 25:34 | I love that the conversation has taken me to the place where I realize that there are certain things that I’m doing in that moment of judgment, right? There are things that I wasn’t fully aware I was doing, which is putting them on some sort of hierarchy in my head of validity, right? I’m basically saying, “Yes. Your life choices are not the life choices that I would make.” And I am saying it to an extent they seem ill-advised, right? That’s what I’m saying to myself. I’m saying that they seem ill-advised. At the same time, I think there’s this underneath even that, there’s a sense of I don’t want to live in a culture in which we are constantly being told that this is the way to have validity. And that’s also problematic to me, right? You’re right, the shoes are worth much more than $250 to the folks who wear them. |

| S. RODNEY 26:39 | But my problem is why is it that the way that your sense of validity gets shunted or gets directed– why is it directed towards these things? I mean, they’re always directed towards different things, right? As Travis had mentioned earlier, the religious ceremonies eat up between 40 and 60 percent of lots of people’s salaries around the world. Right. I guess what I’m looking for is a way for us– I guess what I seek in that moment of looking at folks around me is someone who says, “Actually, I’m just going to do it differently. My sense of validity is not going to be wrapped up in any of the aforementioned things.” Maybe it is wrapped up. I mean, I remember when I used to go to people’s homes, and we used to be able to judge people by the kind of CD collection they had, right? So you go in, you’d be like, “Oh, they have Yaz Upstairs at Eric’s. Okay then. That’s kind of cool. Oh, they listen to UB40. Well, what’s going on with them [laughter]?” |

| S. FULLWOOD 27:47 | I know, I know, I know. |

| S. RODNEY 27:48 | But I do that with books. I’m like if I go to a person’s house and they have like “serious books,” I’m like, “Oh,” my estimation of them starts to rise, right? |

| C.T. WEBB 28:01 | Mm-hmm. |

| S. FULLWOOD 28:02 | Interesting. |

| S. RODNEY 28:02 | So there’s a way in which I guess I’m looking for– |

| C.T. WEBB 28:05 | This is Bourdieu by the way. You’re making Bourdieu’s argument. I mean, this way we draw the way we socially stratify ourselves. |

| S. RODNEY 28:10 | Yeah. I know. I know. Yeah. I know. I know. I know. |

| C.T. WEBB 28:18 | And the thing is I respond the same ways, I feel the same things. In the end, we still sit on the same toilet or squat in the same way, we still have a limited lifespan here on earth, we still are craving and hungry. And no matter what we read, no matter how sophisticated we are, no matter how lettered we are, no matter how righteous and socially armored we are against ethical criticisms, we still are– I’m sorry. Go ahead, Seph. You were going to say? |

| S. RODNEY 28:57 | Minute. |

| C.T. WEBB 28:57 | Oh. |

| S. RODNEY 28:59 | I was [crosstalk]. |

| C.T. WEBB 28:59 | So Seph was very smoothly telling us how much time we had left, and I was thinking he was signaling, so anyway, I’ll leave it at that. I think what Seph is describing and what I feel like Steven is objecting to or pushing back on is that we’re kind of in the same round blue boat. |

| S. RODNEY 29:20 | Yeah. |

| S. FULLWOOD 29:21 | Yeah. The precise summing up of what you just said Travis is funny to me because like we’re all just people, we’re all just trying to get along, why can’t we just get along [laughter]? And I’m like, “Okay. Okay. I think I did bring a knife to a gunfight.” And so now I’m ready to push back on a lot of things. But I think that it was really helpful for you to say some of the points that I made were an argument for capitalism. Like I said, I’m going to pull that apart and kind of think about it because I think I’m interested in individualism that’s not constantly impacting other people’s way of trying to live. And I’m pushing back and thinking about this sort of apocalyptic sensibility that’s pretty much seems to be an element of the way that we think right now. “We need to get this done and we need to have this because the world seems so sure there’s global warming, and there’s this.” And so there’s always been a part of Christianity that feels apocalyptic where it’s like you’ll get your reward in heaven as long as you act right here sort of. And so I just kind of wanted to bring that apocalyptic nature in with the expensive shoes part because who’s to say you’re going to live tomorrow? |

| C.T. WEBB 30:43 | Yeah. Absolutely. |

| S. FULLWOOD 30:43 | So there’s this idea that put money away, put money in this. Dude, I left a job where I was making a decent amount of money to consult, and I made that choice based on kind of what Seph mentioned whatever I was miserable and I wanted to do other things. So my choices largely reflect who I am in this moment. It’s not to say things might change or change in a different way than I anticipate, but I’m very very hypersensitive around who gets to be valued in this culture and who shows up to enforce it socially. |

| S. RODNEY 31:21 | Thank you. And with that, I want to say I think we should move on to talking about what we might talk about the next time. And actually, we had an idea for you to podcast, but I think what you just said is something that is really provocative Steven. I want to pursue it. What does apocalypse mean for us like how does apocalypse change the way we think about a world and about culture? I love that. |

| S. FULLWOOD 31:44 | Well– |

| C.T. WEBB 31:46 | Yeah. Yeah. I was actually going to propose the same thing. So I think that should be our topic next time. |

| S. RODNEY 31:53 | Same pace, same sheet of music. Okay, gentlemen. |

| C.T. WEBB 31:55 | A sense of an ending. |

| S. FULLWOOD 31:58 | An ending that [inaudible]. |

| S. RODNEY 32:00 | Thank you for this. Thank you for enlightening me. Thank you for getting me to think quite seriously about the way I look at the world. |

| S. FULLWOOD 32:08 | Thank you for doing the same for me. |

| C.T. WEBB 32:09 | Same for you too. All right. It was good talking to you guys. And we will speak next week about apocalypses [laughter]. |

| S. FULLWOOD 32:18 | Perfect. Over and out. Have a good day. [music] |

References

First referenced at 28:05

“Pierre Bourdieu was as a French sociologist, anthropologist, philosopher and public intellectual. Bourdieu’s work was primarily concerned with the dynamics of power in society, especially the diverse and subtle ways in which power is transferred and social order maintained within and across generations. In conscious opposition to the idealist tradition of much of Western philosophy, his work often emphasized the corporeal nature of social life and stressed the role of practice and embodiment in social dynamics.” Wikipedia

Episode 0101 – Comedy: Patrice O’Neal, Laughing Because It Hurts

Patrice O’Neal died in 2011, but his comedy is still hot. Stories that turn a bitter reality into laughter is this week’s subject. Should there be a limit on what comedians can say for a joke?

Michael Jackson: The One Percenters of Celebrity

TAA 0069 – Megastars like Michael Jackson seem to be exempted from critiques of their wealth. Rarely do you hear Jay-Z or Tom Hanks referred to derisively as “the one percent.” Why don’t we care about extremes of wealth in our entertainers?

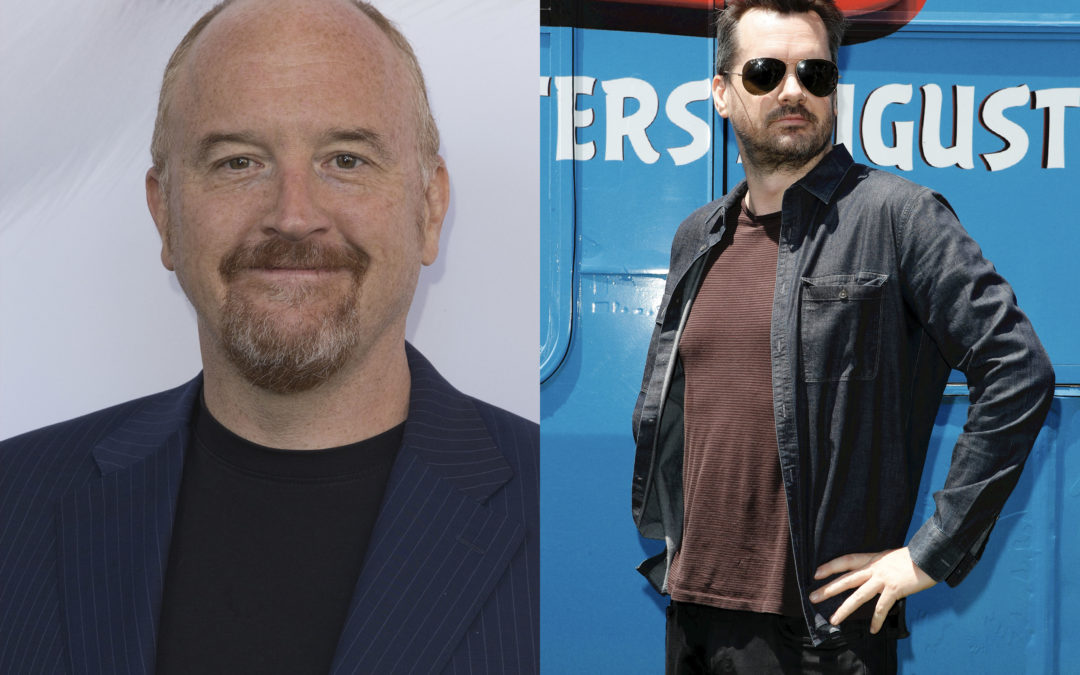

Episode 0098 – Comedy: Offensive Comedy and Its Virtues

There’s laughing at yourself, and then there’s laughing at others. While the former is virtuous the latter is indispensable to group cohesion. In this episode the hosts talk about Jim Jefferies and Louis C.K. What are the limits of comedy?

Pornography, Part VI: Race

TAA 0057 – The hosts conclude their conversation with a discussion of the role of race in the sexual imagination. Why is the white, blonde female body so often the location of heterosexual desire in American culture? Why is the male black body so often fetishized?